The EcoTech Synthesis – how to judge climate change solutions

EcoTech Note: This post summarizes the EcoTech Synthesis and defines key terms.

As web admin of this site and defacto editor of the newsletter, I’ve been unsure about what articles to publish. Climate advocacy touches HUGE swaths of disciplines and stories — far more than I can cover or that our readers have time for. What climate concerns should be presented here?

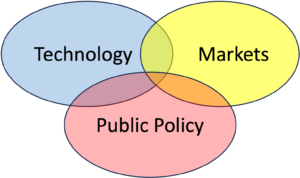

In preparation for a talk I did in mid-August, I focused on the most fruitful paths to address climate change and the policies most likely to advance them. The result is what I call “The EcoTech Synthesis.” I believe it may be a good “scope” for this site and the newsletter derived from it. Here’s an explanation:

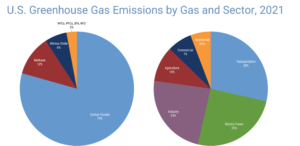

The EcoTech Synthesis seeks to achieve “net zero” by 2050 by substituting “CleanTech” for “DirtyTech.” The difference between them is whether the technology generates greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) or not. See chart below for examples of each kind.

There are five major sectors of human activity that generate GHGs. See graphic.

DirtyTech is usually cheaper than CleanTech; so, people currently use mostly the DirtyTech solutions.

I believe that the transition from DirtyTech to CleanTech will only happen fast enough if the “Green Premium” (defined as the cost of the CleanTech alternative minus the cost of the DirtyTech currently in use) gets to zero, or less.

b) increase the cost of DirtyTech.

Learning Curves

Learning Curves

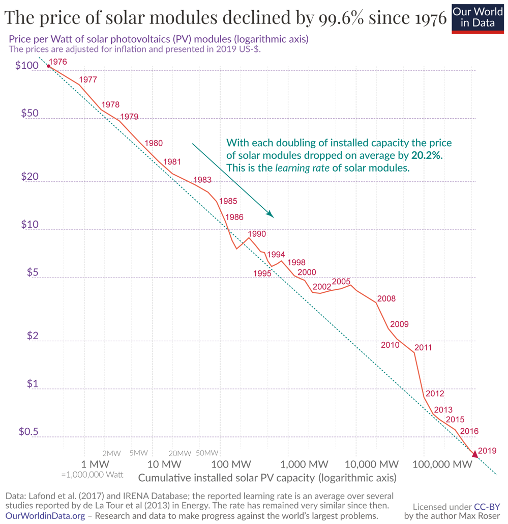

The cost of CleanTech decreases by harnessing discoveries, innovations, experience curves and economies of scale. I’ll refer to all these sources of improved price/performance, including economies of scale, as the “learning curve.”

A good example of a learning curve is shown in the decreasing unit costs of energy from solar panels:

similar geometric rates of improved cost-effectiveness.

What drives learning curves? Answer: money.

What drives learning curves? Answer: money.

Answer: Money. Money comes from investment or from revenues after the technology is productized and sold to a customer. [Green text below is basically “money from investment” and red text below is basically “money from revenues.”]

- Discovery follows from funded science and the scientists who can afford the years of work required.

- Inventions are patented by people seeking fame and fortune.

- Governments fund basic research for various reasons — national security, economic development, general welfare, geopolitical leadership, etc.

- Entrepreneurs start out with investments from “friends and family.”

- Philanthropists back promising developments or “proof of concept” pilots.

- Venture capitalists invest in risky new ventures, seeking outsized returns from the winners.

- “Early Adopters” or market segments with specialized needs buy the CleanTech products when the Green Premium is still pretty high.

- As the learning curve reduces the cost of the CleanTech alternative, the market enters into a virtuous circle: lower costs lead to more sales which lead to even lower costs, etc.

- As this virtuous circle unfolds, later-stage financing sources – private equity, project finance, joint venturers and others – help fund the expansion of infrastructure and growth.

Bottom line: money is the mother’s milk of the learning curve. Some of the money comes from investment. Most of the money, however, comes from revenues or investment that relies on revenue — as early versions of the CleanTech products or services gain market traction.

How does CleanTech “gain market traction” when its Green Premium is still large?

Take a look at the cost and volume of solar panels in the chart above between 2000 (1.0 gigawatt of capacity deployed at $5.00/watt) and the year 2010 (15 gigawatts of capacity deployed at $2.00/watt). Now imagine you are the salesman for the company selling these solar panels. In 2000, how do you sell something at $5/watt when a diesel generator or gas turbine is less than $1.00/watt? Yes, your solar panels will be below $0.60/watt in 2015, but in 2010, you have to sell it for $2.00/watt.

It’s a chicken and egg situation — the more panels you sell, that is, the more the learning curve kicks in, the lower the price gets. The lower the price gets, the more you can sell. But who is the buyer when the price is still relatively high?

While the sales and marketing people are figuring that out, the Chief Financial Officer is trying to keep the lights on. How does s/he raise money from investors and/or use money from early customers to survive? This is the famous Valley of Death financing gap, and virtually every new technology that disrupts an old market has to “get across the Valley of Death” to the point where they are self-sustaining and profitable.

The Valley of Death financing gap

Whole books have been written on how to get across The Valley of Death, and we’ll do another post on it separately. For now, suffice it to say that you either have to find the “niche markets” willing to pay the higher price or show investors that you can get to the lower costs quickly enough that they will subsidize the early sales. Using our solar panel example of a niche market, perhaps remote cabins that are not near convention power lines will buy solar panels at $2.00/watt. Why? Because they don’t have a good alternative. Or they will buy at the premium price because the new technology has a feature (e.g., quiet, clean operation) that’s better than that found in the alternative (e.g., a noisy, sooty diesel generator that requires frequent, inconvenient fuel, which needs to be schlepped to the cabin).

* * * * * * *

Globally, DirtyTech accounts for trillions of dollars of economic activity annually, and it relies on tens of trillions of dollars of existing infrastructure. The bulk of all that activity is paid by consumers and businesses – the private market. The scale and speed of the required transition from DirtyTech to CleanTech is so large that no government can afford to fund it. Consider, for example, that the Inflation Reduction Act — the largest government funding for climate in history — allocated about $560 billion dollars over 10 years, or about $56 billion per year. That is far less than 1% of today’s annual spending on DirtyTech!

Therefore, the CleanTech transition will be grounded in private market success. And that will be driven primarily by reductions in the Green Premium.

This is where government policies become very relevant. Public policy is critically important for driving the discovery, volume and experience components of the learning curve. For example:

- Research and Development. Funding for basic scientific research is mainly provided by the government because general explorations are too risky or remote from market success to attract private investors. Examples include fusion research at Sandia National Labs or grants to universities doing basic research in improved energy density for batteries.

- Mandates. The government can require certain groups to purchase CleanTech alternatives, even when the Green Premium is still positive, e.g., renewable portfolio standards imposed on utilities, requiring them to generate X% of their power using CleanTech by Y date.

- Subsidies. Subsidies, including tax breaks, can reduce the cost of CleanTech alternatives, either by directly subsidizing a buyer (e.g., EVs, heat pumps or solar panels) or by indirectly reducing the cost of supply, (e.g., by a low-interest loan guarantee for new capital equipment or factories to produce the CleanTech solution.)

- Government Purchasing. Government purchasing can choose a CleanTech alternative, even when the Green Premium is still positive, e.g., when the Department of Defense purchases advanced nuclear tech for submarines or the USPS buys EV postal delivery trucks.

- Standards. Setting or facilitating the setting of standards helps reduce costs or complexity by creating safe, universal and interoperable technology with defined quality and risk levels, e.g., those promulgated by NIST, ANSI, and ANSI-accredited Standards Development Organizations (SDOs). Standards reduce costs and stimulate competition, which further reduces costs.

- Infrastructure Support. Government spending can cover or reduce the cost of complementary technologies (e.g., charging stations for EVs, funded by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act).

Those are examples of ways that public policy can foster learning curves and reduce the costs for CleanTech.

The government can also adopt public policies that increase the costs of DirtyTech:

- Stop subsidizing fossil fuels:

- Tax Breaks

- Lease and Royalty Rates

- Fossil Fuel Research and Development

- Impose carbon pricing.

The best way to incentivize the transition is to impose a gradually increasing carbon fee (aka, a tax) at the source (mine, well, pipeline or port-of-entry), coupled with a carbon cashback (aka carbon dividend) and carbon border adjustment mechanism. At Citizens’ Climate Lobby, we advocate strongly for a carbon-fee-and-dividend policy similar to the Energy Innovation Act. - Other public policy tools:

- Prohibitions – e.g., no incandescent light bulb sales, no gas appliances in newly built houses.

- Special fees and taxes – e.g., waste disposal fees on oil from Jiffy-Lube-type businesses; highway taxes; higher license fees on heavier trucks (or exemptions for EV trucks)

- Regulations – e.g., CAFE standards (minimum miles per gallon of vehicles sold).

Acceptance Criteria

Our societal goal is to achieve net zero by 2050, primarily by substituting “CleanTech” for “DirtyTech.” We can achieve this by advocating for public policies that leverage the dynamics of the EcoTech Synthesis, whereby learning curves drive down CleanTech costs, preferably to levels where the Green Premium is zero or less. In parallel, we can institute carbon pricing, preferably in the form of a carbon-fee-and-dividend policy, to drive the cost of DirtyTech higher.

In addition to our primary goal of getting to net zero ASAP, Citizens’ Climate Lobby has other goals, values and constraints that inform our actions. Those additional considerations are best summarized in our three acceptance criteria. To pass muster for CCL support, a public policy must be:

- Effective (in reducing GHGs). This embraces our commitment to science-based policies that work and non-partisan legislation which is likely to be durable for the decades-long timeframes needed.

- Efficient (imposing the least cost for the transition). This informs our commitment to using government resources efficiently and advocating for carbon pricing, which all major economists say is the most efficient way to drive the transition.

- Equitable (fair, not regressive). This informs our commitment to environmental justice and strong support for carbon cashback in the carbon-fee-and-dividend program, as well as a carbon border adjustment to create a “level playing field” internationally for US manufacturers.

Summary

I believe that the EcoTech Synthesis and the public policies that reduce the Green Premium are a suitable scope for what gets addressed in this site and the related newsletter. We will highlight new CleanTech alternatives and their current learning curves that drive the Green Premium lower. When possible, we’ll highlight actions that can increase costs to DirtyTech through a reduction in fossil fuel subsidies and/or the initiation of carbon fee and dividend policies.

When appropriate, I will try to make clear which part of a post touches on the EcoTech Synthesis by adding an “EcoTech Note” in front of the post. See, for example, the EcoTech Note at the top of US Snowboard Champ Pitches Green Shipping for Maersk.