Trees As Medicine; A Downtown Microforest

from Bloomberg, printed as From Louisville, a Push to Plant Trees for Public Health

EcoTech Note: We seldom write about the fourth policy area supported by CCL – “Healthy Forests.” Forests are a natural carbon sink, with nature helping with “carbon capture” and bring NET-zero goals closer. Here’s an effort that seeks to measure the health effects on nearby residents.

A study in the Kentucky city has connected new plantings with health data from nearby residents — a first in urban forestry that researchers call “trees as medicine.”

A decade ago, Louisville earned an unwanted distinction: With sparse tree cover and no ordinances protecting trees on private property, the Kentucky city had the fastest-growing urban heat island in the US.

Since then, Louisville has been exploring a variety of green solutions to extreme heat and air pollution. The city launched assessments to determine how to protect and grow tree cover — and where it was needed the most — culminating in a recent initiative to create an urban forest master plan. In 2023, it earned a $12.6 million federal grant to plant thousands of trees in underserved neighborhoods from the Inflation Reduction Act, which is providing $1.5 billion for urban forestry initiatives.

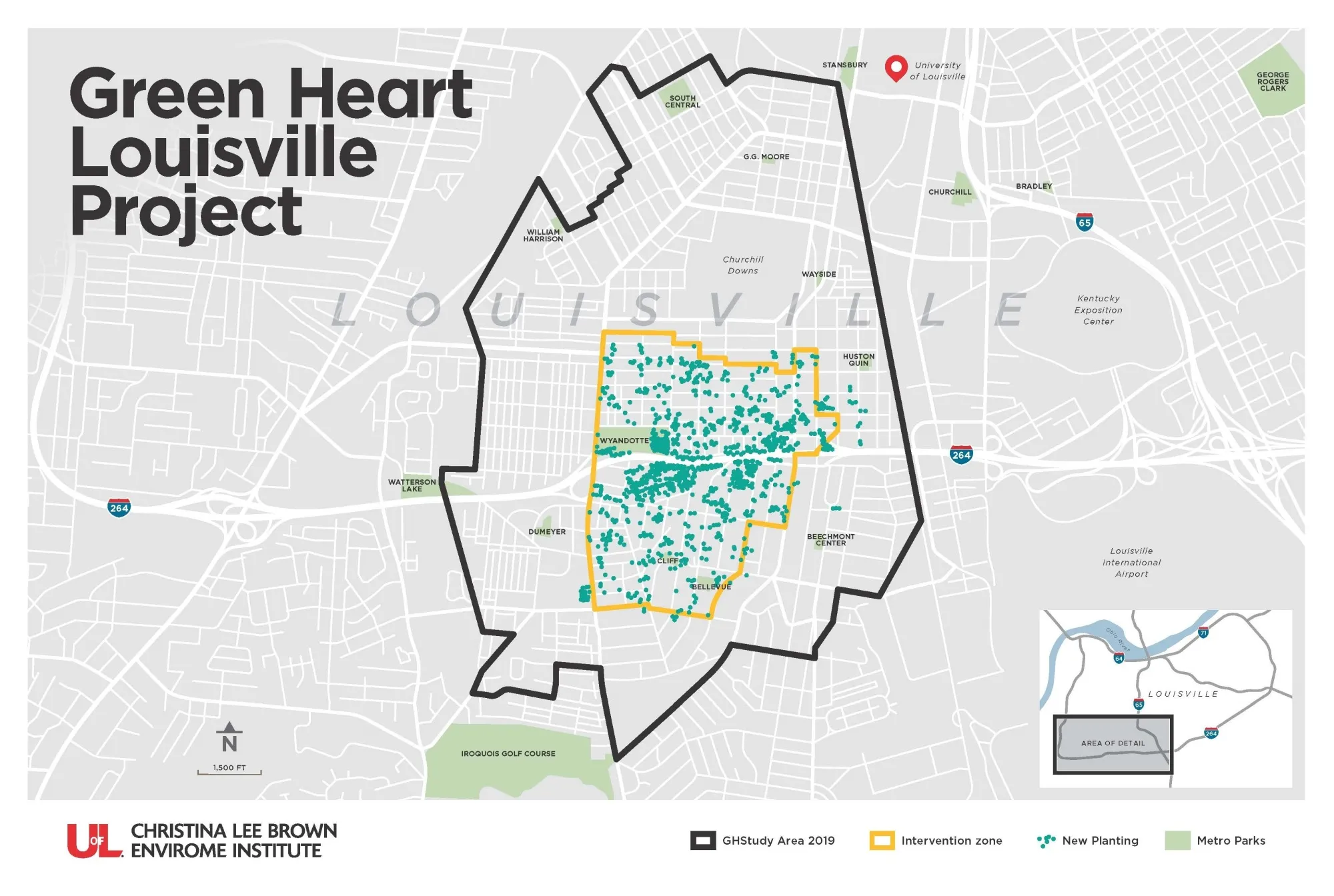

And in late August, scientists at the University of Louisville released the results of a groundbreaking urban tree study. The $15 million Green Heart Louisville project, conducted with the Nature Conservancy and other partners, followed more than 700 residents across a four-square-mile area of south Louisville where about 8,000 trees and shrubs had been planted. According to the study, residents of these newly greened neighborhoods had 13% to 20% lower levels of a blood marker of general inflammation compared to residents in neighborhoods where no new greenery was added. Inflammation is a leading risk factor for heart disease, cancer and diabetes.

On its website, Green Heart Louisville organizers bill the project as “a clinical trial where trees are the medicine.”

Aruni Bhatnagar, the project’s lead investigator and director of the university’s Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute, says that the study is the first to use a clinical trial design — a controlled intervention, rather than the usual observational studies — to probe how adding trees and greenery to urban space affects human health. It’s also the first such study to plant large, mature trees instead of saplings and utilize an evidence-based approach to guide their exact placement in the neighborhoods. Instead of planting based on aesthetics, for example, the team “measured where the levels of air pollution were highest and targeted the planting to those areas,” Bhatnagar said.

The project focused on several neighborhoods that straddle Interstate 264, an expressway built in the 1960s that loops its way around central Louisville. Half of the study participants had household incomes under $50,000, reflecting a national pattern in which high-polluting infrastructure is sited near low-income neighborhoods.

Trees as Medicine

Municipal tree planting programs have become an increasingly popular response to global concerns about rising temperatures in urban areas. Cities like Phoenix and Detroit have pledged to plant thousands of trees, aiming to improve air quality, livability and flood resilience while addressing longstanding inequities that have left marginalized neighborhoods desperate for shade and green space.

As extreme heat becomes more common — and as air pollution continues to exact a deadly toll — urban planners and public health and climate experts are also calling for more creative interventions as well as scientifically robust ways of incorporating nature into the city.

“There is nowhere you can put a tree where it doesn’t improve the situation in terms of cooling and air quality,” said Brian Stone, director of the Urban Climate Lab at Georgia Tech University in Atlanta.

But as the number of trees going into the ground increases, Stone said, cities are lagging in developing the kind of data-driven climate assessments and interventions that would ensure these projects provide maximum benefits for individuals and communities.

“Cities are starting to think of trees as infrastructure,” said Stone, whose team helps cities map their heat risk. “And just as we wouldn’t put in a storm sewer system without really good scientific data about where the flood risk is, we shouldn’t be putting in trees without a good understanding of where the heat risks are.”

A Downtown Microforest

Located in the heart of coal country and long afflicted with high levels of air pollution, Louisville has become something of a leader in data-driven urban tree innovation. After his research revealed the state of the city’s canopy, Stone ended up piloting an approach to urban heat management in the region that his team now uses nationally.

Building on that history, academics and practitioners are expanding the purview of urban tree canopy research, aiming to provide new evidence that trees are core to the health — and wealth — of the city.

Starting in November, for example, the University of Louisville’s Urban Design Studio will intensively plant more than 100 large trees on Founders Square, an underutilized three-quarter acre downtown lot. The goal is to create an instant “microforest” — a pocket-sized green space that can deliver significant local benefits. The forest will serve as a field site to investigate a variety of health and environmental issues tied to microclimates and the urban heat island effect.

“Cities need to figure out how to cool themselves down now, and we can’t plant trees the typical way we always have,” said Patrick Piuma, the studio’s director and the lead on the Trager MicroForest.

Funded in part via a $1 million gift from a local philanthropist, the miniature woodland has a second major objective — a downtown revitalization tool.

As in many US metros, Piuma said, downtown Louisville has struggled to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic and the rise of remote work. A preponderance of surface parking lots not only fosters a bleak urban landscape but has also contributed to temperatures that are 10 to 20 degrees higher than those in outlying areas.

Over the past year and a half, workers have been taking air and surface temperature readings around the microforest site; the team is also analyzing the way people interact with the space and taking blood pressure and other health readings. Once the trees are planted, researchers will take new measurements and compare them to the baseline data.

The hope is the forest, surrounded by a circular walkway, will become an attraction for those who work and live downtown. And if the team can show that it lowers stress levels as well as ambient temperatures, Piuma says, then it could catalyze further greening in the area, drawing more people and businesses downtown.

A different kind of spillover effect will take root during the planned next phase of the Green Heart study, according to Bhatnager. He explained that the “placebo” neighborhoods in the first phase — which didn’t get the new trees — will become the control group, putting them on the receiving end of new greenery. Researchers will investigate optimal tree species to maximize cooling and pollution control, as well as the impacts of greening neighborhoods on residential displacement, home values and gentrification, among other issues.

Spreading the health benefits to more people is another advantage of a study designed as a clinical trial, Bhatnagar said: “If the drug works, there is an intent to treat.”