To fight climate change, environmentalists may have to give up a core belief

To tackle climate, experts say, environmentalists have to embrace big energy projects. Fast.

Right now, many roadblocks stand in the way of building wind, solar, and the transmission lines that can carry their power to city centers. And while Democrats have a bill in the works to speed that sort of permitting, most environmentalists oppose it — because it could also promote oil and gas development.

“We’re going to have to build a lot more of everything clean,” said Josh Freed, the director of climate and energy at the center-left think tank Third Way. “The United States has an infrastructure building crisis. We can no longer build anything big — let alone big and ambitious — in a reasonable time frame.”

To reach net-zero carbon emissions, according to a study by Princeton University, wind farms will have to spread across the Great Plains and the Midwest, covering an area equal to at least the states of Illinois and Indiana. Solar panels will sparkle across an area at least as large as Connecticut. And thousands of miles of high-voltage transmission lines will need to be built to carry all that power from where it’s generated — mostly in rural parts of the country — to urban centers far away.

And these projects need to be up and running soon. According to an analysis by the DecarbAmerica Project, solar and wind power in the U.S. will have to double in just the next eight years.

At the moment, however, a miasma of confusing regulations and local opposition have stymied many of these plans. Residents blocked the project to build wind farms off the coast of New England for decades, complaining it would ruin their ocean views. A transmission line from Pennsylvania to Maryland was blocked by Pennsylvania landowners who argued that the line wouldn’t provide sufficient benefits to their state.

Now a deal between Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) and Senate Democratic leaders could streamline energy permitting. During negotiations over the Inflation Reduction Act, the giant health and climate spending bill that passed Congress in August, Democrats promised Manchin that they would pass a separate bill this fall, to speed up the permitting process for building energy infrastructure — both fossil fuel and clean.

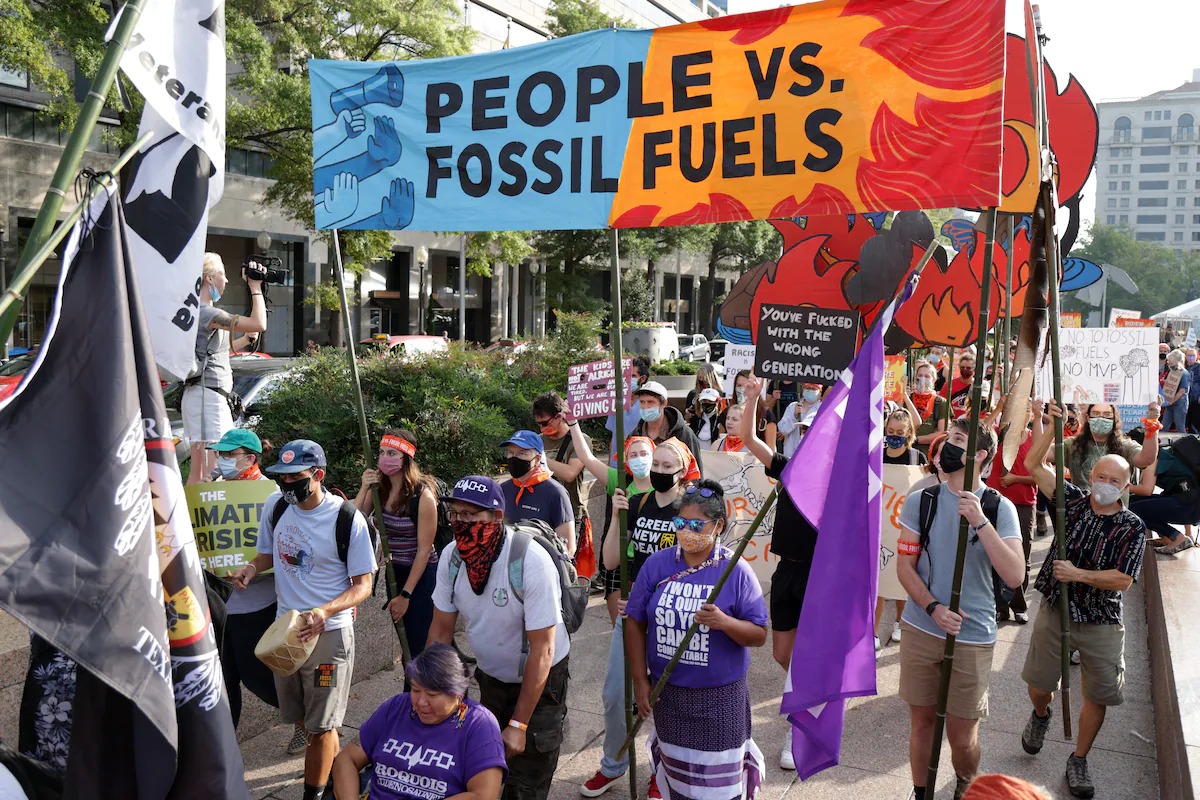

Some environmental groups have blasted the deal, arguing that it would expedite a key priority of Manchin’s, the Mountain Valley Pipeline — a 300-mile pipeline that would transfer natural gas from West Virginia to Virginia — and other fossil fuel projects. “Prolonging the fossil fuel era perpetuates environmental racism, is wildly out of step with climate science, and hamstrings our nation’s ability to avert a climate disaster,” more than 650 environmental groups wrote in a letter sent to Congress in late August. Meanwhile, a group of Appalachian activists are planning a march on D.C. next week to protest the permitting reform deal and the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

But energy experts argue that, depending on the structure of the deal, permitting reform could help the U.S. switch over to clean energy — and ultimately benefit renewables more than fossil fuels.

For example, Liza Reed, the research manager for electricity transmission at the center-right think tank Niskanen Center, argues that building a more connected electric grid is absolutely essential to cut carbon emissions. Wind and solar energy, she points out, are rarely located in the same place where power is needed. “We need to build transmission very quickly and very dramatically,” she said. “There’s no two ways about it.”

One thing that could help, Reed argues, is giving the federal government authority to approve the construction of big, high-voltage transmission lines. At the moment, power lines have to get approval from every state that they cross, including states that may not benefit much from having gigantic power lines weaving over their homes and buildings. Federal authority would allow the government to rubber-stamp transmission lines without getting into the local and state regulatory morass. (Similar authority already exists for natural gas pipelines.)

Romany Webb, a senior fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, says that law is critical to making sure that communities aren’t adversely affected by energy and pipelines. But, she added, “I do think there’s ways to streamline the NEPA process to make it work better for some of these large renewable energy projects.”

Green groups, however, still have reservations.

“Whatever the proposed project is — whether it’s a pipeline or a highway or a solar farm — it should be subject to the same commonsense review process,” Mahyar Sorour, a deputy legislative director for the Sierra Club, said in an email. “If we want these projects to move forward faster, we shouldn’t be weakening environmental laws, but investing more resources into the agencies and staff.”

It remains unclear exactly what the permitting bill will say, and whether it will pass. It needs 60 votes under Senate rules to pass, so some Republicans will have to get on board. And some Democrats may not vote for it, since any permitting reform agreement will also leave the door open to further fossil fuel extraction.

“The devil is in the details,” Freed said.

Without reform, though, many believe that the clean-energy transition will not happen at the pace the country needs.

But the shift will be a change for an environmental movement that has spent decades learning to block, not to build. It will require careful analysis of how to rapidly expand wind, solar, and even nuclear with community input.

“With the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, the environmental movement broadly has endorsed building,” Freed said. “Now the question is: ‘How?’”