Sea Level Rise Growing in American South

One of the most rapid sea level surges on Earth is besieging the American South, forcing a reckoning for coastal communities across eight U.S. states, a Washington Post analysis has found.

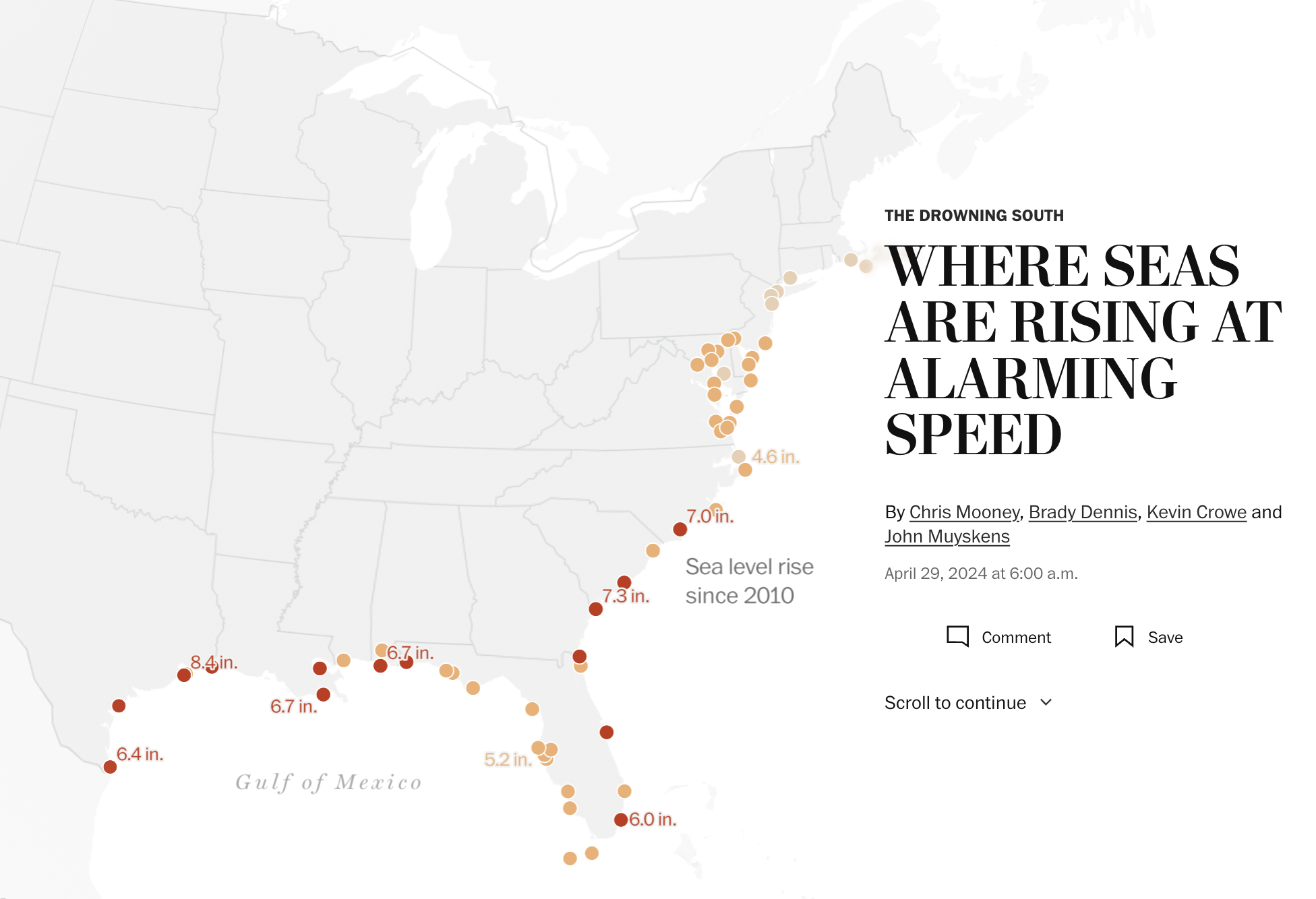

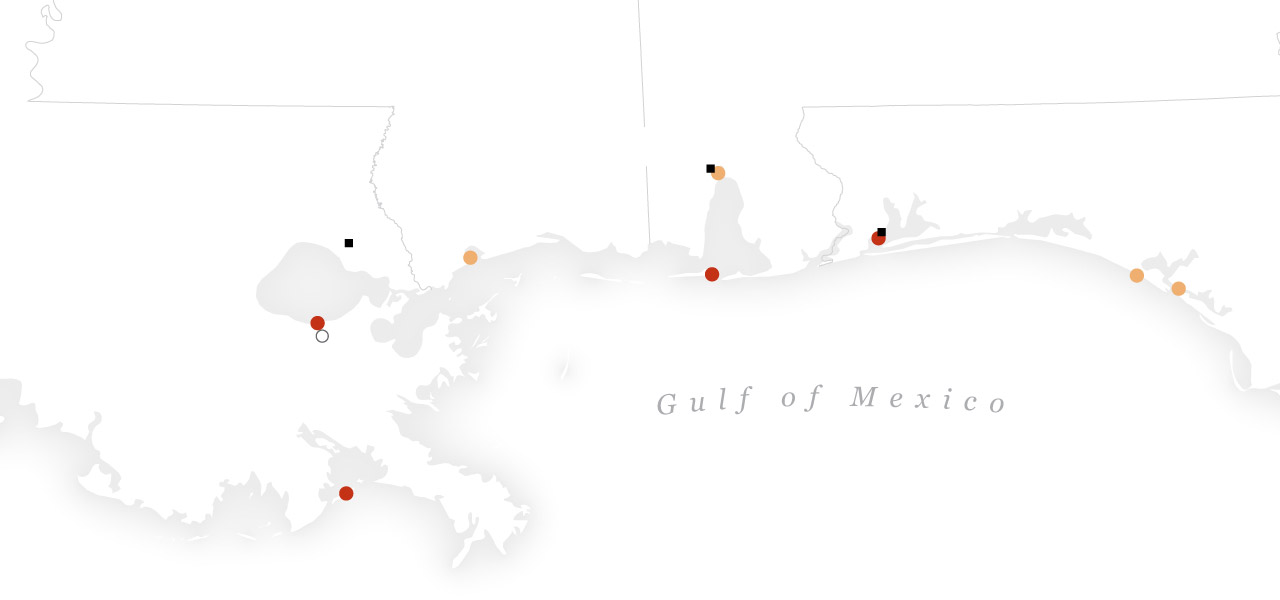

At more than a dozen tide gauges spanning from Texas to North Carolina, sea levels are at least 6 inches higher than they were in 2010 — a change similar to what occurred over the previous five decades.

Scientists are documenting a barrage of impacts — ones, they say, that will confront an even larger swath of U.S. coastal communities in the coming decades — even as they try to decipher the precise causes of this recent surge.

The Gulf of Mexico has experienced twice the global average rate of sea level rise since 2010, a Post analysis of satellite data shows. Few other places on the planet have seen similar rates of increase, such as the North Sea near the United Kingdom.

“Since 2010, it’s very abnormal and unprecedented,” said Jianjun Yin, a climate scientist at the University of Arizona who has studied the changes. While it is possible the swift rate of sea level rise could eventually taper, the higher water that has already arrived in recent years is here to stay.

“It’s irreversible,” he said.

As waters rise, Louisiana’s wetlands — the state’s natural barrier against major storms — are in a state of “drowning.” Choked septic systems are failing and threatening to contaminate waterways. Insurance companies are raising rates, limiting policies or even bailing in some places, casting uncertainty over future home values in flood-prone areas.

Roads increasingly are falling below the highest tides, leaving drivers stuck in repeated delays, or forcing them to slog through salt water to reach homes, schools, work and places of worship. In some communities, researchers and public officials fear, rising waters could periodically cut off some people from essential services such as medical aid.

THE DROWNING SOUTH

End of carousel

While much planning and money have gone toward blunting the impact of catastrophic hurricanes, experts say it is the accumulation of myriad smaller-scale impacts from rising water levels that is the newer, more insidious challenge — and the one that ultimately will become the most difficult to cope with.

“To me, here’s the story: We are preparing for the wrong disaster almost everywhere,” said Rob Young, a Western Carolina University professor and director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines.

“These smaller changes will be a greater threat over time than the next hurricane, no question about it,” Young said.

In December, Charleston, S.C., saw its fourth-highest water level since measurements began in 1899. It was the first time on record that seas had been that high without a hurricane. A winter storm that coincided with the elevated ocean left dozens of streets closed. One resident drowned in her car. Hundreds of vehicles were damaged or destroyed, including some that were inundated in a cruise terminal parking lot.

The average sea level at Charleston has risen by 7 inches since 2010, four times the rate of the previous 30 years.

Jacksonville, Fla., where seas rose 6 inches in the past 14 years, recently studied its vulnerability. It found that more than a quarter of major roads have the potential to become inaccessible to emergency response vehicles amid flooding, and the number of residents who face flood risks could more than triple in coming decades.

Galveston, Tex., has experienced an extraordinary rate of sea level rise — 8 inches in 14 years. Experts say it has been exacerbated by fast-sinking land. High-tide floods have struck at least 141 times since 2015, and scientists project their frequency will grow rapidly. Officials are planning to install several huge pump stations in coming years, largely funded through federal grants. The city manager expects each pump to cost more than $60 million — a figure that could eclipse the city’s annual tax revenue.

For this analysis, The Post relied on tide gauge data, which reflects the rise in sea level and sinking of land. Satellite data, which solely measures the height of oceans, was used for global measurements.

“The phenomenon is so new, we still don’t necessarily even have the vocabulary for it,” Christopher Piecuch, a sea level scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, said of the unrelenting nature of flooding confronting more and more communities. “This is something that quite literally didn’t happen two decades ago.”

But it undoubtedly is happening now. The number of high-tide floods is rapidly increasing in the region, with incidents happening five times as often as they did in 1990, said William Sweet, an oceanographer for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“We’re seeing flooding in a way that we haven’t seen before,” said Sweet, who leads the agency’s high-tide flooding assessments. “That is just the statistics doing the talking.”

Projections suggest that the flooding of today will look modest compared with what lies ahead. High-tide floods in the region are expected to strike 15 times more frequently in 2050 than they did in 2020, Sweet said.

Here are glimpses at three spots along a roughly 200-mile stretch of the U.S. Gulf Coast that are already confronting this new reality:

Mobile, Ala., 5.9 inches of sea level rise since 2010

THE INEQUITY OF RISING WATER

‘People of color are more likely to experience flooding’ — and the city is working to adapt.

The inequities of the past and the changing threats of the present are colliding in this centuries-old port city.

Here, as in other cities, the legacy of unequal federal housing policies dating to the 1930s, known as redlining — a discriminatory practice that in particular targeted Black Americans — left minority and low-income residents confined to certain areas. Over time, they faced the heavy burden of industrial pollution. Some of these same neighborhoods are now grappling with rising waters.

“The acknowledgment and acceptance of these historic inequities and their present-day impacts is a necessary, critical step,” city officials wrote in a recent report, adding: “[P]eople of color are more likely to experience flooding in Mobile.”

That’s partly due to relatively flat topography that allows higher water levels to travel farther inland and cause more severe flooding than in the past. The report said that many of the affected neighborhoods are low-lying and have decaying storm water systems, making them particularly vulnerable.

Rodneyka Lofton has lived in the same house on St. Emanuel Street, along a swath of Mobile’s heavily industrialized waterfront, for “a majority of my life,” she said.

“Sometimes, it makes me feel not safe,” Lofton said one morning of the floodwaters that often submerge her street and other roads that lie about a quarter-mile from the Mobile River near where it ends at Mobile Bay.

“On my street, and on the back street over there, it looks like a small lake. And a lot of cars get stuck,” said Lofton, a nursing assistant. Only a handful of residents remain here, amid rows of semitrailers, a junkyard and a large container facility.

Along some areas of the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, recent research suggests, low-income and minority residents are likely to face a deepening burden as climate change fuels rising seas and more intense rainfalls.

“Flood risk is not borne equally by all,” wrote the authors of a 2022 study in the journal Nature Climate Change. In particular, they wrote, “The future increase in risk will disproportionately impact Black communities, while remaining concentrated on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.”

Near Lofton’s home, recent data suggest the burden already is increasing.

The tide gauge at the nearby Mobile State Docks has registered about 6 inches of sea level rise since 2010.

Texas Street, around the corner from Lofton’s home, was once again inundated one morning earlier this year. A car was inching through deep water.

Rain had fallen the previous night, but the flooding was destined to linger due to high seas. A coastal researcher from the University of South Alabama, Bret Webb, had recently outfitted a sensor in one of the street’s drains. It showed that the base of the drain is now frequently lower than the waters in the Mobile River, preventing drainage.

As Mobile’s chief resilience officer, Casi Callaway works to gird the city’s residents and its infrastructure for the growing stresses posed by climate change and other challenges. She said Mobile has been steadily upgrading roads and the pipes beneath them — and aims to do so near Lofton’s home.

But she said it will take at least $30 million to fix drainage problems in an area where some storm water pipes are over a century old and made of wood. The city has applied for several grants to perform the work but has not yet received funding.

“Every dollar we invest should be a dollar spent preparing for what is coming,” said Callaway, who previously headed a local environmental group.

Over a century of history and memory also lie in the path of floodwaters.

That is evident in the Old Plateau Cemetery in Africatown. The neighborhood in Mobile was founded by formerly enslaved people who arrived in 1860 on the Clotilda — the last known slave ship to leave Africa for the United States — and their descendants.

The historic burial ground dates to 1876, and appears to have been warped by sinking land and repeated flooding. Many graves now rest at angles. Some are sunken and fill regularly with rainwater, and those at the lowest-lying points are in disrepair.

While multiple factors probably play a role in the cemetery’s flooding problems, there are two ways rising seas can make them worse, said Alex Beebe, a geologist at the University of South Alabama who has studied the cemetery. As waters in Mobile Bay and the Gulf of Mexico rise, the water flowing downhill through Africatown to the coast will have more trouble escaping, he said. A higher ocean is also causing groundwater tables to rise, making it harder for rainfall to penetrate the soil.

For Yuvonne Brazier, the flooding is just part of a bigger inequity in Africatown, which also is hemmed in by heavy industry.

Brazier’s grandfather and her sister, who died when she was young, are buried in the cemetery, along with many of the founders of the community.

But Brazier can no longer find the graves. She used to be able to sit on her mother’s front porch and see the cemetery where her loved ones were buried. That familiar landscape has grown less familiar over time.

“It’s all different now,” she said.

St. Tammany Parish, La., 6.1 inches of sea level rise since 2010

A $5.9 BILLION PLAN TO HOLD BACK WATER

The U.S. government wants to protect a fast-growing region from flooding. Homeowners don’t agree on the plan.

Cody Bruhl looked out over the boat launch in Madisonville, which he had reached only after driving through a mile of flooded road in his pickup truck. Behind him, fish swam through a submerged parking lot.

Here on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, residents can drive 24 miles south across one of the world’s longest bridges to reach New Orleans. But they lack that city’s human-made protections against water. Now high tides had caused yet another flood, an increasingly common occurrence due to 6 inches of sea level rise in the lake — which is directly connected to the Gulf of Mexico — since 2010.

Bruhl, a 37-year-old avid duck hunter, loves this place. But he also worries about its future.

“That’s what I’m trying to get my own grip around for myself and my family,” said Bruhl, a member of the St. Tammany Levee, Drainage and Conservation District whose home flooded in 2021’s Hurricane Ida. “If we’re going to continue to live here, we’ve got to find a protection that can mitigate a lot of this, because at some point it becomes not sustainable anymore.”

It is a predicament reverberating throughout the vulnerable parish, home to about 275,000 people. A home building boom since Hurricane Katrina has replaced vast stretches of land with asphalt and other surfaces that can worsen flooding. Some communities, crisscrossed with canals, are difficult to defend. Mandeville has a sea wall and Slidell has a few inland levees. But it’s nothing like the protections engineered for New Orleans.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers wants to change that. It has outlined plans to spend an estimated $5.9 billion protecting St. Tammany Parish alone.

Under the plans, which are years from becoming reality, Slidell would get its own nearly 19-mile-long levee and floodwall, and officials would raise parts of Interstate 10. A significant expenditure would go toward raising or flood-proofing more than 6,400 structures, mostly homes, in the parish. One of those, Bruhl said, would be his own.

The changes, the Corps has said, are aimed at mitigating repeated flood events that have “caused major disruptions, damages, and adverse economic impacts to the parish.” While the plan factors in sea level rise, it is centrally targeted at stopping hurricanes and river-driven floods — not necessarily the sunny-day flooding that happens with increased regularity.

In parts of St. Tammany, homeowners remain divided about the massive undertaking.

Donna and Kevin McDonald, who run a construction company in the Slidell area, are “on the fence” about the project, Donna said. They’re not sure it is the solution, but they certainly recognize the problem.

Part of the filming of “Where the Crawdads Sing,” a hit 2022 film set in North Carolina, took place in May 2021 behind their home on Bayou Liberty, where moss dangles over the dark waters from the branches of live oaks.

The film crew built a shack along the dock as part of a set that would represent the bait shop of Jumpin’, one of the film’s characters. But soon, heavy rains coincided with a days-long tidal surge in Lake Pontchartrain and the set was inundated, delaying production. The surge was the 10th-highest water level recorded at the tide gauge in New Orleans, and the highest that didn’t come from a hurricane or tropical storm.

It was just another reminder of how water — more and more of it — is altering life here.

Kevin McDonald has lived in this same house for all his 71 years. The home never flooded before 1995, he says. Not even in historic hurricanes like Camille and Betsy.

“Now,” he said, “we’ve flooded seven times.”

Pensacola, Fla., 6.5 inches of sea level rise since 2010

WATER WITH NO PLACE TO GO

The city is one of many in the region contending with outdated and overmatched infrastructure systems.

In the early morning, the rising tide in Pensacola Bay swallowed an outfall pipe that is supposed to empty water from a downtown neighborhood called the Tanyard.

Water sat near the tops of the drains along S. De Villiers Street — a telltale sign of the higher ocean creeping backward up pipes and a predicament plaguing a growing number of coastal communities.

“As far as the water’s ability to get out, it’s going to have to literally take on Pensacola Bay,” Brad Hinote, the city engineer, said as he surveyed the scene.

It wasn’t raining. But when it rains hard enough, waters swallow this street entirely.

Nearby residents know the unceasing battle better than anyone.

“The water tries to go down, but it has no place to go,” Gloria Horning said outside the home she has owned on S. De Villiers Street since 2016. “The infrastructure is so low, so old, it just explodes because it can’t take the water. And it doesn’t take but a couple of inches for that to happen every time.”

Horning has put up silt fencing along her property to try to stop the wake from the cars that drive through standing water, sending waves across her yard. A longtime environmental and social justice activist, Horning has focused on flooding issues since water first entered her home in 2016.

Horning said her home last flooded during a strong rainstorm in June. But it is the more incessant nuisance floods that keep her on edge.

“Now, when it rains, I’m getting up in the middle of the night, packing my dogs up and going,” said Horning, who has pushed for more stringent environmental and flood regulations in the city. “Because just a few inches of rain, and I’m sitting in water and sewage.”

Pensacola is hardly an outlier. As sea levels rise, experts say, there are many cities with outdated and overmatched infrastructure systems.

“Storm water flooding is getting worse and is unsustainable,” said Renee Collini, director of the Community Resilience Center at the Water Institute. “Almost all our systems are gravity fed, and they were built out a long time ago.”

Hinote, like his counterparts facing similar predicaments, has struggled with how best to solve the changes that are happening — and the even more dramatic ones scientists say are on the way.

“Everybody says, ‘Well, put in pumps.’ And that’s definitely a solution,” he said. But pumps can fail, especially in saltwater environments. And, he added, “they are exorbitantly expensive.”

Pensacola, one of the nation’s oldest cities, has offered some residents the opportunity to elevate their homes or take buyouts, Hinote said. It has considered elevating the roadway through the neighborhood, but that might only push more water toward nearby houses. And it has requested an engineering analysis to study solutions in the area — and their cost.

“It’s a difficult position to be in as a city official,” Hinote said. “My goal is to fix this situation.”

But, as he gazed over the flood-prone neighborhood, he saw no easy answers.

“When you’re up against an obstacle …” Hinote said as he looked down at an overmatched drain, “how do you overcome it?”

About this story

Jahi Chikwendiu contributed to this report.

Design and development by Emily Wright.

Photo editing by Sandra M. Stevenson and Amanda Voisard. Video editing by John Farrell. Design editing by Joseph Moore.

Editing by Anu Narayanswamy, Katie Zezima and Monica Ulmanu. Additional editing by Juliet Eilperin. Project editing by KC Schaper. Copy editing by Frances Moody.

Additional support from Jordan Melendrez, Erica Snow, Kathleen Floyd, Victoria Rossi and Ana Carano.

Methodology

The Washington Post used monthly tide gauge data for 127 gauges from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for relative mean sea levels in the United States. This is adjusted for seasonal signals for ocean temperature, currents, and other marine and atmospheric variables.

For its analysis, The Post relied on dozens of tide gauges along the coasts of the United States, measurements that are affected both by the rising ocean and slow but persistent movement of land. It also took into account satellite data for global sea level rise, which measures ocean heights independent of land movement.

Annual means for two time periods — 1980 to 2009 and 2010 to 2023 — were calculated. Only gauges that had at least eight months of data for a given year and 70 percent of the years were used. Three gauges used in this analysis are not currently in service but had sufficient data for the 1980 to 2023 time period to include in the analysis.

A linear regression model was applied to the annual means for each gauge to determine the trends for each time period and calculate an annual rate of relative mean sea level rise. Because readings from tide gauges are also influenced by the rising or sinking of land, these findings are referred to as changes in relative mean sea level.

To analyze changes in sea level around the globe, The Post used data based on satellite altimetry readings produced by NOAA. Annual means were calculated for 1993 through 2023 for the global data and for each ocean. The Post applied a linear regression model estimating the annual rates of change in mean sea level for each ocean and the global average. The data from the satellite altimeters are measures of ocean height independent of any land movement, or absolute means.

The Post is displaying data for tide gauges on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts that showed significant trends in mean sea level change from 2010 to 2023.

Scientists have studied regional trends in sea level rise, including Jianjun Yin and Sönke Dangendorf, among others. The Post’s analysis builds on this body of work and compares trends for the 2010-2023 and 1980-2009 time periods to drive home the rate of acceleration in recent years. The Post also presents the trends for each tide gauge included.