Parent Participation in Climate Justice Efforts Is Rising

“We [scientists] have been telling you guys for so many decades that we’re headed towards fucking catastrophe,” Kalmus said. The clip went viral, probably in part because when Kalmus told the cameras (and waiting cops) that he was committing nonviolent civil disobedience “for my sons,” he began to weep — and didn’t stop. Their protest, he said brokenly, was for “all of the kids of the world, all of the young people, all of the future people.”

Kalmus is one of thousands of parents worldwide organizing around a similar rallying cry: We love our children. We won’t let you wreck their world.

A couple decades ago, there were few, if any, family-focused environmental organizations, let alone the kind of parent-led climate justice groups now confronting polluters and the systems of racism, colonialism, patriarchy and extractive capitalism that enable them. In the U.S., Mothers Out Front began to organize in several states in 2013 and, two years later, mothers in some chapters of the climate action group 350.org launched subgroups centered around families and the parental imperative to protect children from harm.

Then, in 2018, Greta Thunberg and her school strikes took the world by storm. Though some young people were already leveraging their moral authority in court to demand that adults stop trashing their future, the Fridays For Future school strikes — and Thunberg herself — received spectacular media attention. They electrified the burgeoning global youth climate movement and inspired the offshoot group Parents For Future Global that now boasts hundreds of parent-led grassroots groups in 23 countries. (You can join the next global strike September 23.) Other mom-led groups have since sprung up worldwide, including in the U.K., India, Pakistan and Canada.

I asked four parent-focused organizers how one might begin to parent toward climate justice.

Brooklyn-based Chandra Bocci, a fellow with the international parent-climate network Our Kids Climate and Parents For Future Global, says that parenting toward climate justice is not about “a perfect, zero-waste lifestyle.” Given humanity’s short time frame to slash emissions enough to keep warming under 1.5 degrees Celsius, she advocates collective empowerment and action that’s targeted strategically. “Showing children that we have a window where we can do something — and that we are doing something — is so important.”

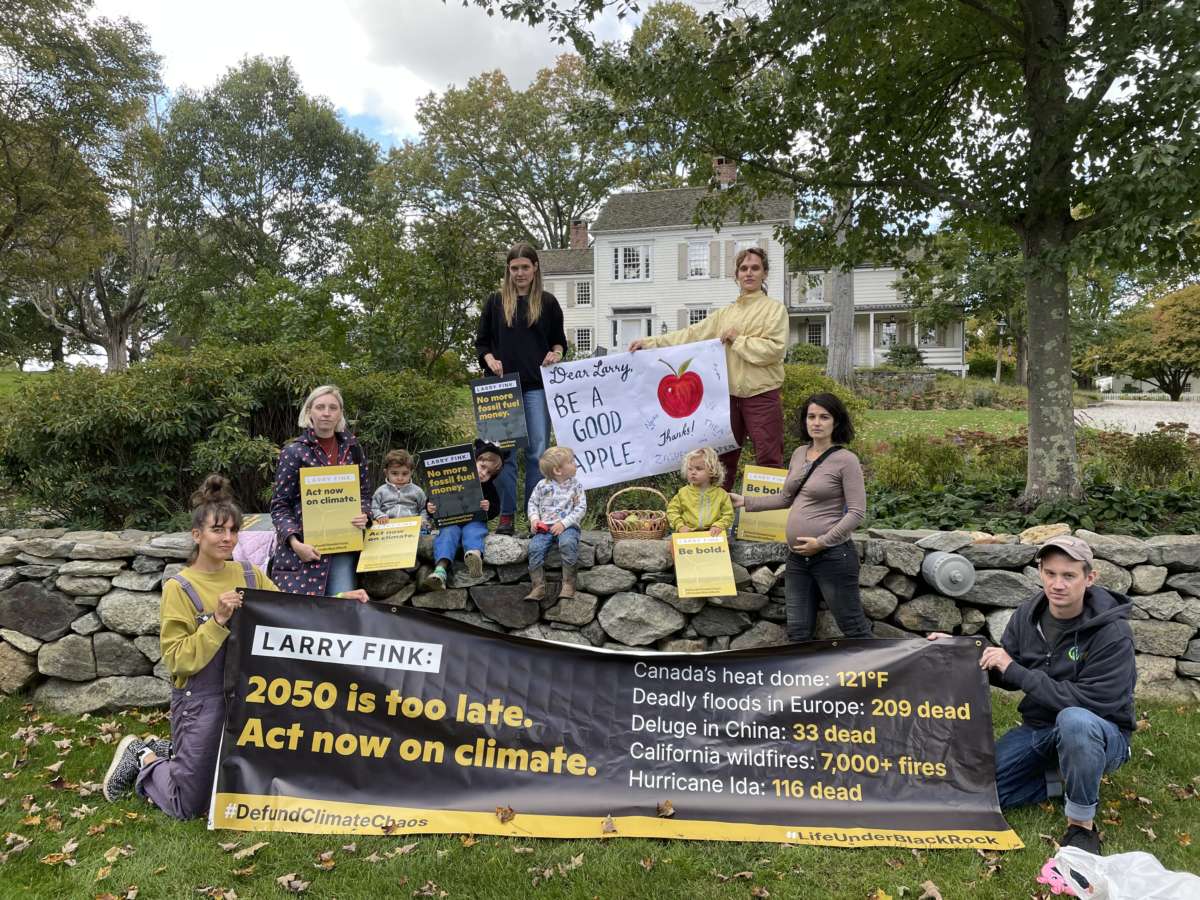

For Bocci and her preschooler, that meant joining parents from Climate Families NYC at a 2021 protest in front of the home of Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager. BlackRock, with its nearly $260 billion invested in coal, oil and gas projects worldwide, had long been a focus for Bocci and other parent climate organizers. When they learned that Fink lived near several of them, they felt a responsibility to appeal directly to the father of three to use his outsize influence to divest BlackRock from climate destruction.

“I think that was only the second time he had talked in person with any activist group,” Bocci said, recalling that Fink came out to meet them. “Because of our position as parents with kids, we have a different approach and a different kind of moral authority from other activists showing up. We keep very positive, but we’re not scared, either.”

Parents working in some conservative communities can face massive challenges on the climate justice front, says Winona Bateman, executive director of Missoula, Montana-based Families For a Livable Climate (FLC). In Montana, she says, “we have folks trying to make voting more difficult for our tribal communities and Indigenous nations. There are definitely racist, dog whistle, political signals that get thrown around in our state. That’s a challenge because those are triggers for people.”

Bateman is not daunted. “The data around how people feel about climate change and the danger it presents to the world is pretty strongly in our favor,” she says. “Even in Montana, over 60 percent of people agree it’s happening and there’s strong support for corporate action and renewable energy as part of our future.”

To engage that 60 percent and “create community for climate action in Montana” (FLC’s stated mission), FLC offers education on creating zero-waste schools, talking to kids about the climate crisis and moving from climate despair to action. Those ready for political action can petition utilities to transition to clean energy or support the kids taking the state of Montana to trial next year for violating their right to a clean and healthful environment.

But a predominant focus, says Bateman, is helping parents feel comfortable talking about climate justice with people across cultural and political divides: “People need space to shift, and they can’t get there if no one can have a conversation with them about it. If you just yell at them, they’re not going to be able to shift.”

On September 27, FLC will offer a virtual discussion with Katherine Hayhoe about her 2021 book Saving Us: A Climate Scientist’s Case for Hope and Healing in a Divided World. Hayhoe, who has children, is widely praised for helping climate advocates find common ground with a broad range of people based on shared values.

A challenge for several parent climate action groups, including Bateman’s in Montana, is that they’re sometimes made up of all or mostly white, middle-class women. Bateman doesn’t shy from this fact, or the daily work required to create a just and equitable future for everyone.

“We try to make sure we’re bringing lots of different perspectives and voices into the work we’re doing and to how we’re understanding things.” To deepen her own understanding, Bateman, a descendant of settlers in North Dakota, took a “deep dive” into her own family tree. “My family settled along the Knife River of North Dakota; the lands of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation (Three Affiliated Tribes).”

“The challenge for white people in the movement,” she said, “is to step up and engage folks who are not thinking about how climate is disproportionately impacting people of color and people of low income.”

Lorna Pelly, based in British Columbia, tries to raise kids who understand the world isn’t fair and contribute toward correcting injustices. In her work with For Our Kids (FOK), a network of over 20 active parent-led chapters across Canada, she begins with recognizing that the climate crisis impacts people unequally. “It will always be the lower-income people or countries that are affected the most and have a harder time rebuilding after climate disasters,” Pelly said. “I’ve never been able to sit well with that, knowing that it’s the more developed countries causing [more of] the carbon emissions.”

FOK trains parents in “Curious Climate Conversations” and supports Wet’suwet’en Land Defenders, Indigenous communities fighting Coastal Link Gas and its attempt to force a new pipeline through their unceded territory. Many parents have been shocked, says Pelly, to learn about the racism of Canada’s police force, and FOK now offers workshops on raising anti-racist children. (You can join this September 17 workshop.)

For the growing number of parent groups in the Global South, movement-building is both more urgent and more difficult, organizers say.

“Parenting toward climate justice means something very different to us here in the Global South than it does to you in the North,” says Amuche Nnabueze, a Nigerian organizer with Parents For Future Global. “We are already suffering the effects of climate change in every aspect of our lives. There is so much poverty. We do not even have water, clean water. There are droughts and floods. Rivers are drying up.”

During our interview, the power went out twice, plunging Nnabueze into darkness. Nigeria is well-known for its entrenched political corruption that makes it hard for citizens of the densely populated African nation to even discuss human rights or feel safe traveling to events in other cities for fear of kidnapping. Many people are hungry, says Nnabueze, and lack health insurance. All of this together can create indifference when she reaches out to parents through local organizations, her academic and social circles and her church, urging them to join, for example, the upcoming global climate strike on September 23.

“Poverty drives this indifference,” Nnabueze says, so she works to connect where she can, spearheading advocacy campaigns and encouraging others to lifestyle changes such as reducing plastic consumption.

“Parents really connect to lifestyle changes, so we talk about things they can do.” Climate advocacy in Nigeria can’t be only about climate strikes because, she says with a laugh, “we are not really sure what the government will do.”

Nnaueze’s three children join the parent-led events and her daughter, 17, organizes Green Teens Africa, which focuses on sustainable lifestyle skills. “We parents are supporting them through sharing our ancestral and Indigenous knowledge about growing crops subsistently, waste management, permaculture and more based on our Indigenous circular economy model.”

Nnabueze felt boosted by the year-long Parent Climate Fellowship that gave her training, financial support and the opportunity to travel to Glasgow last year for COP26. It was powerful, she said, to join other climate organizers and bring her voice to the global stage.

Nnabueze continues to network with parent climate organizers worldwide, informing the work of parents in the Global North through regular online meetings with international parent networks such as Our Kids Climate and Parents For Future Global.

She and many other Global South parent organizers are impacting groups in the Global North, including all of those mentioned above, who do their best to learn, educate their members, and then try to help in their own communities.

In her work with New York City parents, Bocci tries to follow the lead of environmental justice-centered organizations. “We’re not reinventing the wheel. We’re really paying attention and reaching out and collaborating and partnering and following calls to action from BIPOC and working-class [groups] in our state,” she said.

New York Renews, a statewide coalition of over 300 grassroots groups, centers environmental justice in their work and has developed a clear legislative agenda. “A lot of what we do is follow their lead and just jump on their campaigns and amplify them. Then we show up in support. We ask, ‘How can we help?’”