Monday was the Earth’s hottest day in at least 125,000 years. Tuesday was hotter.

Why a sudden surge of broken heat records is scaring scientists

Scientists say to brace for more extreme weather and probably a record-warm 2023 amid unprecedented temperatures

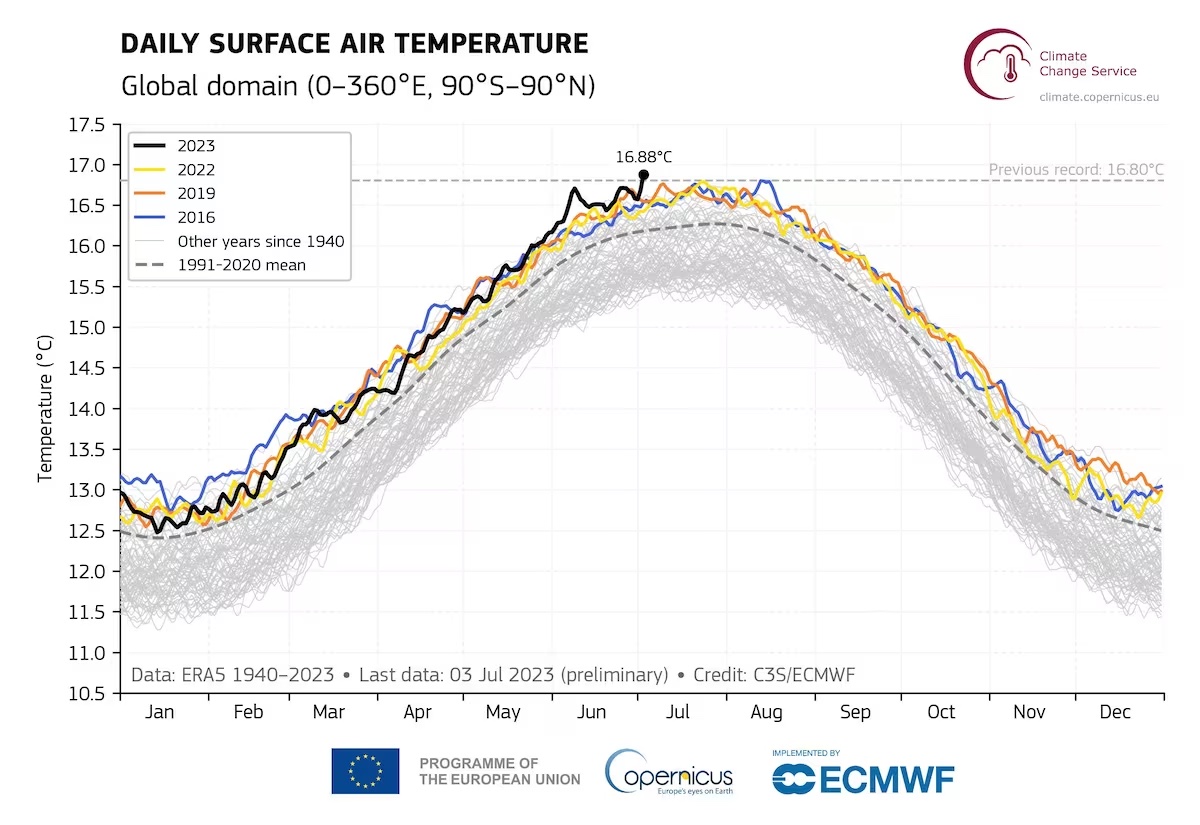

And then, on Monday, came Earth’s hottest day in at least 125,000 years. Tuesday was hotter.

“We have never seen anything like this before,” said Carlo Buontempo, director of Europe’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. He said any number of charts and graphs on Earth’s climate are showing, quite literally, that “we are in uncharted territory.”

It is no shock that global warming is accelerating — scientists were anticipating that would come with the onset of El Niño, the infamous climate pattern that reemerged last month. It is known for unleashing surges of heat and moisture that trigger extreme floods and storms in some places, and droughts and fires in others.

But the hot conditions are developing too quickly, and across more of the planet, to be explained solely by El Niño. Records are falling around the globe many months ahead of El Niño’s peak impact, which typically hits in December and sends global temperatures soaring for months to follow.

“We have been seeing unprecedented extremes in the recent past even without being in this phase,” said Claudia Tebaldi, an earth scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Wash. With El Niño’s influence, “the likelihood of seeing something unprecedented is even higher,” she said.

In recent weeks, weather extremes have included record-breaking heat waves in China, where Beijing surpassed 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit) for the first time, and in Mexico and Texas, where officials were once again struggling to keep the electricity grid up and running.

Wildfire smoke that has repeatedly choked parts of the United States this summer is a visible reminder of abnormal spring heat and unusually dry weather that have fueled an unprecedented wildfire season in Canada, which saw both its hottest May and June.

Ocean heat is to be expected during El Niño — it is marked by unusually warm sea surface temperatures along the equatorial Pacific. But shocking warmth has developed far beyond that zone, including in the North Pacific, around New Zealand and across most of the Atlantic.

Marine heat wave conditions covered about 40 percent of the world’s oceans in June, the greatest area on record, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported. That footprint is only expected to grow, forecast to reach 50 percent of ocean waters by September.

It’s not just that records are being broken — but the massive margins with which conditions are surpassing previous extremes, scientists note. In parts of the North Atlantic, temperatures are running as high as 9 degrees Fahrenheit above normal, the warmest observed there in more than 170 years. The warm waters helped northwestern Europe, including the United Kingdom, clinch its warmest June on record.

New data the Copernicus center published Thursday showed global surface air temperatures were 0.53 degrees Celsius (0.95 degrees Fahrenheit) above the 1991-2020 average in June. That was more than a tenth of a degree Celsius above the previous record, “a substantial margin,” the center said.

Antarctic sea ice, meanwhile, reached its lowest June extent since the dawn of the satellite era, at 17 percent below the 1991-2020 average, Copernicus said. The previous record, set a year earlier, was about 9 percent below average.

The planet is increasingly flirting with a global warming benchmark that policymakers have sought to avoid — 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels. It has, at times, been surpassed already this year, including in early June, though the full month averaged 1.36 degrees above an 1850-1900 reference temperature, according to Copernicus. The concern is when long-term averages creep closer to that threshold, Buontempo said.

“The average will get there at some point,” he said. “It will become easier and easier, given the warming of the climate system, to exceed that threshold.”

Halfway through 2023, the year to date ranks as the third warmest on record, according to Copernicus.

At the start of 2023, it appeared possible, if only narrowly, that the year would end up Earth’s warmest on record. For now, 2016 holds that benchmark, heavily influenced by a major El Niño episode that arrived the previous year.

But as El Niño has rapidly developed — and as signs of extreme warmth have spread across the planet — the odds of a new global temperature record have increased. Robert Rohde, lead scientist at Berkeley Earth, estimates the probability has climbed to at least 54 percent — more likely than not.

“The warmth thus far in 2023 and the development of El Niño has definitely progressed faster than initially expected,” Rohde said in a message.

Climate scientists diverge over whether a new global temperature record should be a focus of concern. Flavio Lehner, an assistant professor at Cornell University, likened it to tracking sports scores.

“It’s not necessarily meaningful,” Lehner said. What matters, he said, is that “we have a long-term trend that is a warming climate.”

For others, though, records are a sign of trouble, nearly as hard for people to ignore as the incessant waves of wildfire smoke.

“It just raises everybody’s awareness that this is not getting better; it’s getting worse,” said Jennifer Francis, senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts. “My hope is that we’ll raise alarm bells by breaking a new record and that will help motivate people to do the right thing and stop ignoring this crisis.”

For Tebaldi, records underscore a need to both reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prepare communities for new weather extremes. After all, she said: What was once unprecedented will one day become the norm.