Let Joe Manchin have his pipeline

from Slow Boring

Less activist chum, more focus on stuff that matters

I tend toward the school of thought that says the NEPA review process is basically bad. [See “The Case for Abolishing the National Environmental Policy Act” in Liberal Currents magazine.] Like any process that makes it easier to delay or block things, you can certainly point to specific situations in which it is used to delay or block things that deserve to be delayed or blocked. But it also delays and blocks lots of things that shouldn’t be delayed or blocked. And if you want to transform the nation’s energy system, then delay is fundamentally not your friend. The infrastructure for a fossil fuel economy already exists; the infrastructure for a net zero economy does not. Reforming the permitting process to make it easier to build the economy we need is good and important, and it continues to be good and important even if a fair permitting deal also lets some fossil fuel projects go forward.

We shouldn’t kid ourselves: we still lack clarity on Joe Manchin’s actual comprehensive vision for permitting, his red lines, and the full extent of what he’s open to.

But it is clear that Manchin wants a deal to get one specific project, the Mountain Valley Pipeline, done. This pipeline is very close to completion, despite a lot of litigation (though its litigation woes are far from over), and the Biden administration is under pressure to kill it. This is not a renewables project, and Manchin’s interest here is not in abstract reform. West Virginia has more capacity right now to produce natural gas than it does to deliver gas to customers. Manchin wants the MV Pipeline complete so that more gas can flow from his home state into Virginia and beyond. Green activists have spent a lot of time over the past decade organizing to stop pipelines, and they don’t want to stop organizing to stop pipelines, so they don’t like this deal with Manchin.

And I think the proximate issue in this whole fight isn’t that the activists are wrong about big-picture abstract permitting reform, but that they are specifically wrong about the MV Pipeline. They should let Manchin have what he wants on this topic, and the movement should find something better to do with its time than trying to block natural gas pipelines. The goal of the climate movement should be to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and pipeline-blocking is not an effective strategy for accomplishing this. But pipeline-blocking as a strategic priority is deeply embedded in the movement because the successful kneecapping of the Keystone XL pipeline has become embedded as a foundational myth of the climate movement.

The Keystone XL fight

About a decade ago, climate activists were highly mobilized around one very specific issue — pressuring Barack Obama to use discretionary federal authority to block the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline that would have brought Canadian oil into the United States.

There were a lot of left vs. center-left writer fights about this in which center-left writers made the following points:

- The emissions reductions from blocking Keystone XL were minimal.

- Blocking Keystone XL was badly alienating important labor unions and dividing the progressive movement.

- Most of the oil that was not moved via Keystone was moved via train instead, which was more dangerous and more hazardous to the environment.

These takes often urged activists to trade Keystone for something that was more important or argued for the movement to focus on more important things — if Democrats had a majority in Congress, they could pass a climate bill.

The superficial rhetoric around Keystone didn’t make much sense, and the level of focus on it was completely absurd. But the smartest people in the environmental movement said that Keystone was important for organizing. The philosophy on the left is that to make progress on issues, you always need to be organizing. And the way you organize is that:

- You always need to have something that you are demanding.

- You need to be demanding something not of enemies who will blow you off, but of friends who potentially care about what you think.

- You need to be demanding something that your friends can already give you, not something they could give you if they defeated your enemies in elections.

The point of this is that if you, as a movement, accept an idea like “be polite and quiet and help us try to win House seats,” then you are a weak movement with no power. What you need to be saying is “you, elected officials, must give us this thing that is already in your power or else we will say you are bad people.” So while blocking Keystone could not meaningfully reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, it was something Barack Obama could do unilaterally. So instead of organizing on behalf of things that would be effective at combatting climate change, the movement organized on behalf of something that would be effective as organizing chum and successfully killed the pipeline.

Chum addicts

The problem with orienting your whole movement around something that doesn’t make sense as an organizing tactic is that the tactic doesn’t work if you tell everyone that’s why you’re doing it. So high-level climate wonks and policy writers like me get told the information that “Keystone is really about organizing” to try to discourage us from writing pieces making the point that factually, anti-Keystone politics are not effective climate policy. But the point of that is to mislead people inside and adjacent to the climate movement.

Of course this also becomes a form of anti-organizing.

Unions with concrete jobs at stake end up with their interests sacrificed not on the altar of climate change (a genuinely important issue) but on the altar of climate-adjacent organizing. Elected officials like Manchin who are pressured between local state politics and climate science learn that top environmentalists aren’t trustworthy.

But worse, once the organizing chum works you have a movement that demands ever more chum. In my neighborhood, there is a group of people who like to put organizing posters on the lampposts. For a while when energy negotiations were proceeding at a slow pace in the Senate, the posters all called for Joe Biden to declare a climate emergency. Declaring a climate emergency would not have meaningfully impacted climate change, but it was a thing Biden could do and therefore good organizing chum. The posters didn’t say “just give in to Manchin’s demands and get something done.” They said we needed a climate emergency. Then when talks came down, new signs went up calling for protestors to disrupt the congressional baseball game in order to demand climate legislation. When legislation was active, they didn’t want to talk about legislation — they wanted the emergency as chum. But then when legislation was dead, the baseball protest became new chum.

But then the Inflation Reduction Act happened!

At that point the sign could have said “hey, good for everyone, now we’re going to go home and urge Catherine Cortez-Masto to say and do anything necessary to get re-elected.” But that’s not organizing. You need new chum. So the new chum is that Democrats should stab Manchin in the back and double-cross him on this pipeline. It’s an idea that doesn’t make sense because it’s coming from a corner of the universe that rejects the idea that its object-level campaign goals should make sense.

The pipeline is fine

There is, at the end of the day, nothing wrong with the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

Yes, it will lead to more natural gas being burned. And natural gas causes CO2 emissions. But how many additional net emissions will be generated by completing the MV Pipeline? It’s not clear. The opponents never offer a net emissions impact estimate because, I think, it would be embarrassingly low and potentially zero.

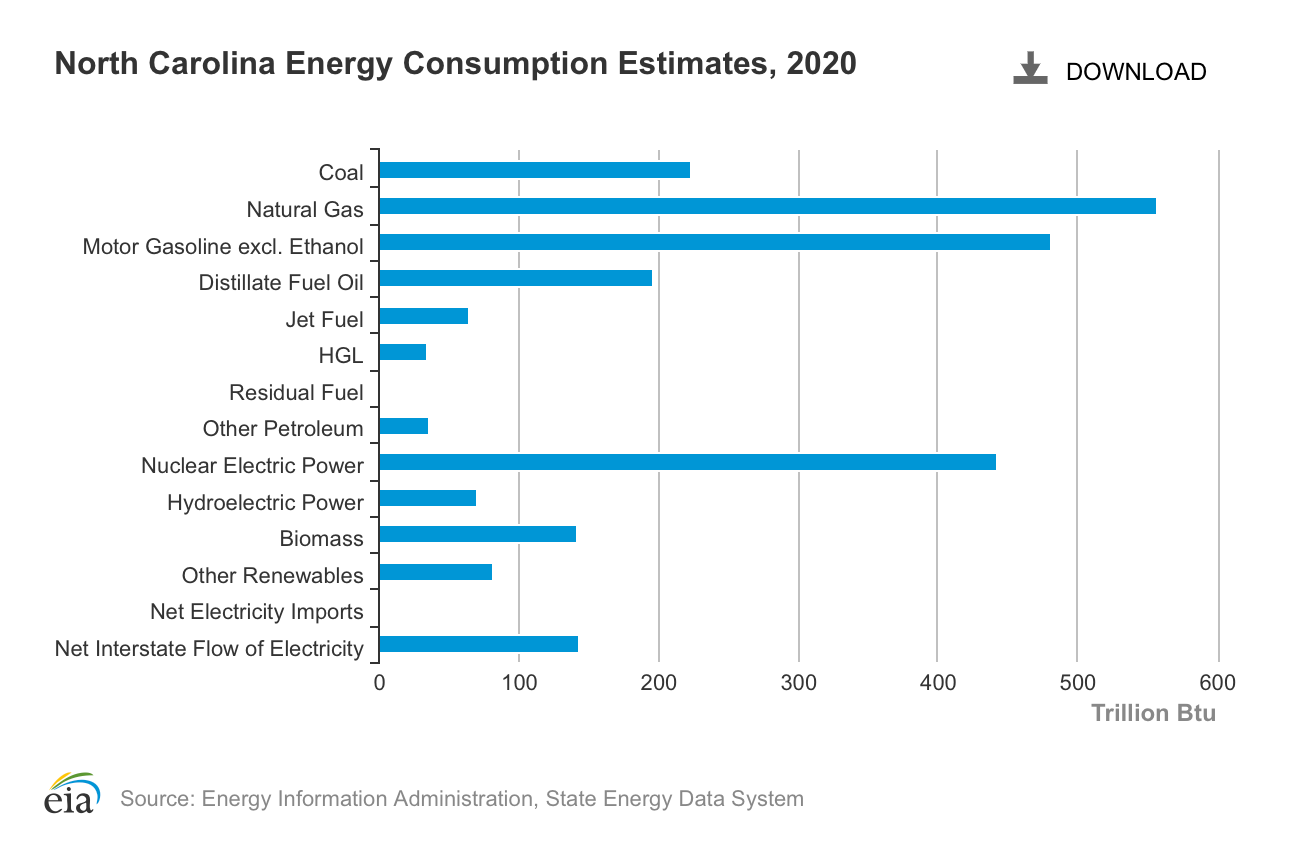

Virginia, where the gas would go, still uses some coal, which is dirtier than gas.

And next to Virginia is North Carolina, where they’re burning lots of coal.

In addition to competing with coal in electricity generation, gas competes with oil for home heating. These days in the U.S., oil is overwhelmingly used in the northeast, where this pipeline isn’t going. But there is some heating oil still used in Virginia.

So at least some of the increased gas consumption associated with the pipeline is going to make emissions lower rather than higher. I don’t think we need to be utopian and say the pipeline will actually reduce emissions, but it’s pretty clear that the Obama-era gas boom reduced emissions (thanks to gas/renewables complementarities), and the impact of the pipeline is ambiguous.

My larger point about this, though, would be that if blocking the pipeline reduces emissions, the causal pathway for doing so would be by raising consumer energy prices. If you do this with a carbon tax (I know, I know) it’s politically challenging, but the upside is the government gets tax revenue that can be used to protect the poor or to subsidize clean energy. By contrast, if you try to cut emissions by raising prices by blocking a pipeline, you generate windfall profits for incumbent owners of fossil fuel infrastructure and you displace fossil fuel production from the United States to other countries.

Gas exports are good

Back in 2018, when natural gas was cheap, the Natural Resources Defense Council put out a big release arguing that the real purpose of MV and other proposed pipelines was to export gas through LNG terminals:

To export natural gas, it is first transmitted to a facility where it is liquified into a product called liquefied natural gas (LNG). It is then shipped overseas, regasified, and finally pumped into another pipeline in the destination country. US LNG export terminals are being built along our coasts. There are currently two operating in Louisiana and Maryland and four new terminals under construction in Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. Total U.S. LNG export capacity is scheduled to increase from 1.4 Bcf/d in 2016 to 9.5 Bcf/d by the end of 2019.

But there are 21 additional LNG export facilities proposed for the lower 48 and under review at the U.S. Department of Energy. If approved, these facilities would export more than 32 Bcf/day—about 40 percent of the natural gas produced each day in the US in 2017.

LNG export terminals need pipelines to bring them natural gas. That’s where new pipelines come in.

NRDC names the Mountain Valley pipeline as one of four nefarious projects being undertaken with the evil intention of exporting natural gas overseas.

Given today’s geopolitics, pipeline opponents will probably be less invested in that anti-export rhetoric — right now, the Biden administration is racing to increase America’s LNG export capacity to try to rescue Europe from Vladimir Putin’s gas weapon. The fact that our LNG capacity is constrained is, at the moment, preventing domestic gas prices from rising too much. But the more we are able to export to Europe, the more U.S./European prices will converge. Still, the United States is going to want more natural gas to substitute for Russian production.

Beyond the specific wartime exigencies, though, the current war situation is a reminder of two powerful facts.

One is that blocking X metric tons of domestic natural gas production reduces global gas consumption by much less than X, because global markets are at least partially interlinked. When we don’t build a pipeline from West Virginia, we end up with more gas pumped by Qatar, Russia, and Venezuela.

But second is that when countries lack access to gas, they don’t just decide to get by with renewables alone and defer industrialization until they’re ready to do it in a 100 percent renewable way. Amidst Vladimir Putin’s “keep it in the ground” campaign, EU emissions are rising even as energy prices spike because Europeans are reopening coal plants and embracing wood-burning stoves as a result of the gas shortage. This isn’t a specific problem with blocking gas production in the context of war with Russia — it’s a conceptual failing of supply-side climate policy. Unless you can actually get people to say “it’s good that Russia is cutting off our gas supplies, this makes us better off,” then supply-side policy is a conceptual dead end. You need measures to reduce consumption, and you need measures to increase the supply of cleaner energy. Blocking pipelines is never going to get the job done.

Beyond activist chum

Back in the Keystone days, activists would often push back against center-left wonks by saying “look, it’s not like any of your ‘actually this other thing is more important’ points have any practical meaning — nothing is happening legislatively, there are no deals to be struck.”

Ten years ago that might have been true. But in 2022, a deal was struck. Manchin agreed to enact a historic emissions reduction bill, and what he wanted in exchange was a pipeline that is a medium-sized deal for his home state and a nothingburger for global emissions.

Give the man what he wants.

Meanwhile, it’s not like there’s nothing else to work on. To achieve a 100 percent clean electricity grid, we are going to need technological breakthroughs in batteries, in advanced geothermal, in advanced nuclear, and ideally in more than one of those. There are permitting barriers to interregional clean energy transmission, creating utility-scale wind and solar, geothermal exploration, and getting NRC approvals for new reactor designs. Some cities are moving to ban gas hookups in new construction, which is good for the environment. Even better for the environment would be to get the jurisdictions that are adopting clean building codes to massively upzone so that lots of affordable new green buildings get built.

We need policy work on freight rail electrification. We need technical work on aviation and maritime shipping.

And we need to recognize that renewable energy isn’t really like magic that just flows from nature. Solar panels and batteries need to be manufactured out of minerals that are mined and refined, and the United States needs to increase the supply of those minerals. We probably want to do more refining here at home so China doesn’t control the whole advanced battery market.

In short, we are not out of things to do. We’re not out of technical problems to work on or policy changes to push for — including some policy changes that are deregulatory in nature and potentially appealing to conservatives. Lots of people are working on these problems, which is great. And what we need from funders and movement leaders is to support those people and to encourage more people to join them in tackling problems that make a big difference. Picking fights about causes that don’t make sense on the merits in order to “organize” keeps the movement trapped in a toxic cycle of picking fights that don’t make sense. Let Joe Manchin have his pipeline. Thank him for the unprecedented investments in zero-carbon energy. And let’s solve the next set of problems.