Hole in the ozone layer to fully heal by mid-century

From Wapo as “Ozone layer continues to heal, a key development for health, food security and the planet, U.N. study says“

By Scott Dance

January 9, 2023

A new assessment of Earth’s depleted ozone layer released Monday shows that efforts to repair the vital atmospheric shield are working, according to a panel of U.N.-backed scientists, as global emissions of ozone-harming chemicals continue to decline.

As a result, the ozone layer — which blocks ultraviolet sunlight from reaching Earth’s surface — continues to slowly thicken.

Restoring it is key for human health, food security and the planet. UV-B radiation causes cancer and eye damage in humans. It also damages plants, inhibiting their growth and curbing their ability to store planet-warming carbon dioxide.

Scientists said the ozone’s recovery should also serve as proof that societies can join to solve environmental problems and combat climate change.

“Ozone action sets a precedent for climate action,” World Meteorological Organization Secretary General Petteri Taalas said in a statement. “Our success in phasing out ozone-eating chemicals shows us what can and must be done — as a matter of urgency — to transition away from fossil fuels, reduce greenhouse gases and so limit temperature increase.”

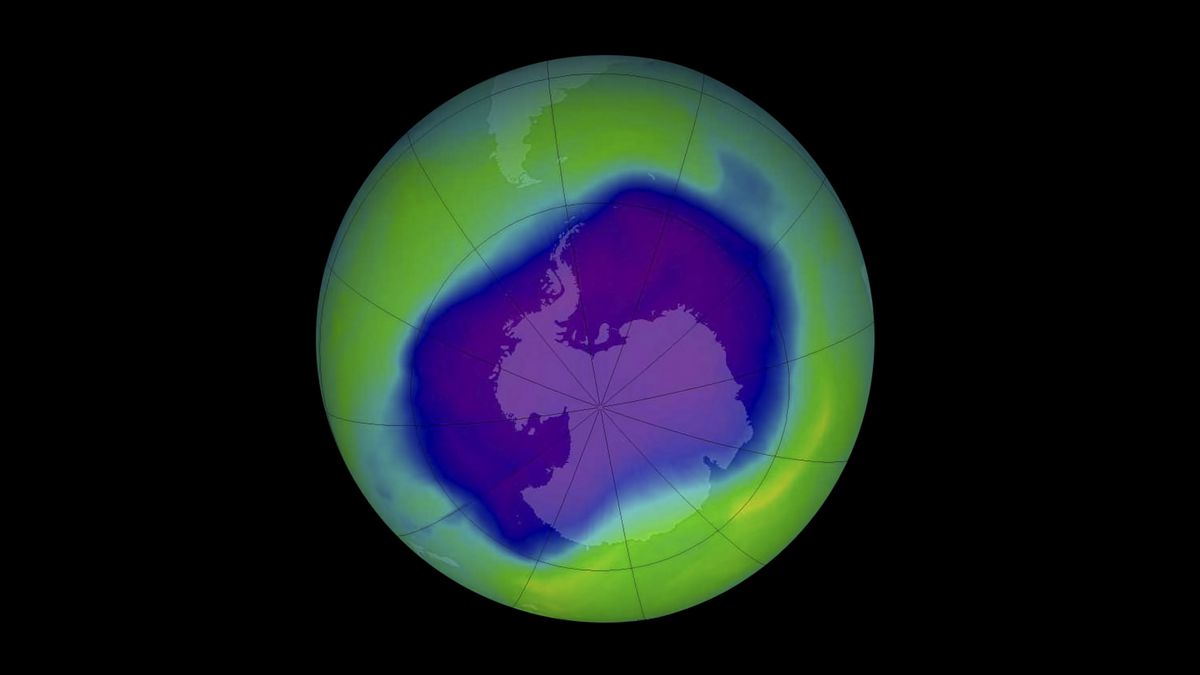

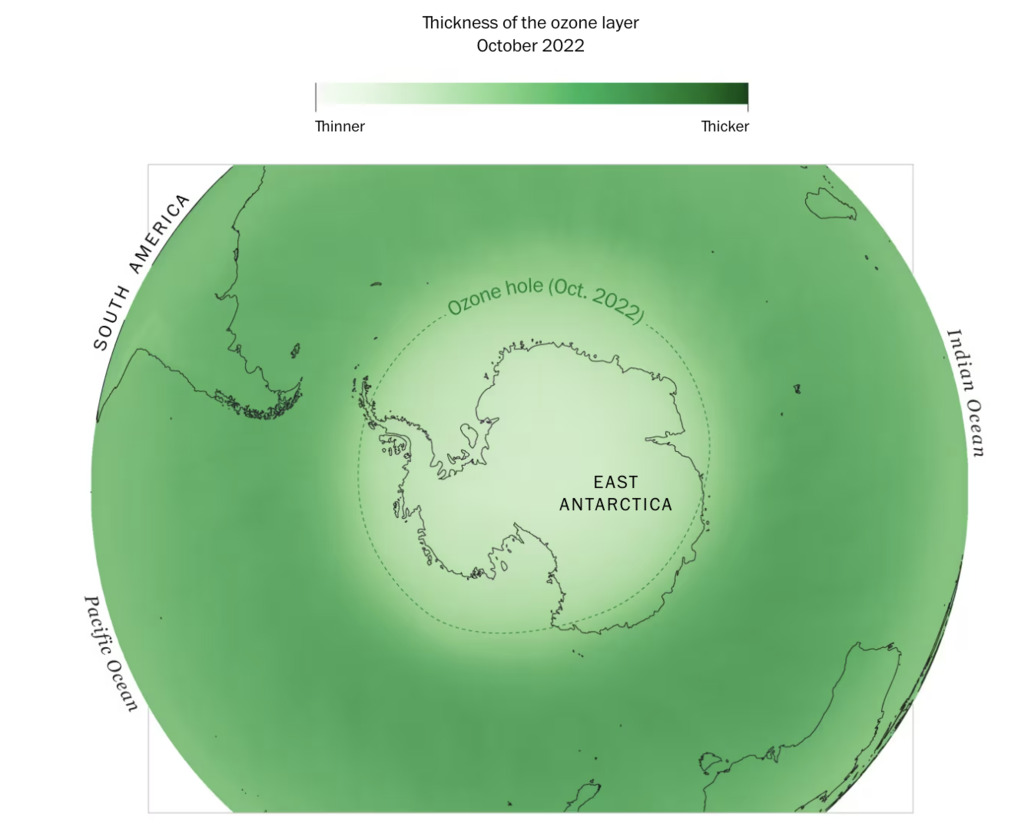

At this rate, the ozone layer could recover to 1980s levels across most of the globe by the 2040s, and by 2066 in Antarctica, the report concludes. Ozone loss is most dramatic above the South Pole, with an ozone “hole” appearing there every spring.

Those improvements will not be steady, scientists stressed, given natural fluctuations in ozone levels and the ozone-inhibiting influence of volcanic eruptions like the massive one from underwater Pacific Ocean volcano Hunga Tonga a year ago.

But scientists said the latest ozone data and projections are nonetheless further proof of the success of the Montreal Protocol, the global 1987 agreement to phase out production and use of ozone-depleting substances.

Meg Seki, executive secretary of the U.N. Environment Program’s Ozone Secretariat, in a statement called the findings “fantastic news.”

A recent decline in observed levels of the chemical known as CFC-11, in particular — which as recently as 2018 had been observed at higher-than-expected levels and traced to China — is proof that societies can collaborate to address a confounding environmental problem, said Martyn Chipperfield, a professor at the University of Leeds who serves on the scientific panel.

“That turned out to be another success story,” he said. “Communities came together and it was addressed.”

Ozone is a molecule made of three oxygen atoms, and it proliferates in a layer of the stratosphere about 9 to 18 miles above the ground. It can exist at ground level, too, where it is a product of air pollution on hot summer days and considered a health hazard. But in the atmosphere, it serves as an essential shield protecting Earth’s life from harmful ultraviolet radiation.

In the same way that UV lights eradicate pathogens like the virus responsible for covid-19, the sun’s radiation would make it impossible for life to thrive on Earth if not for the ozone layer’s protection. UV-B, a high-energy form of solar radiation, damages DNA in plants and animals, disrupting a variety of biological processes and reducing the efficiency of photosynthesis.

The Montreal Protocol, which has been approved by every country in the world, protects the ozone by outlawing the manufacturing and use of substances that destroy it when they come in contact with it in the atmosphere. That largely includes a class known as chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, which contain ozone-depleting chlorine and were used in refrigerators, air conditioners and aerosol cans.

The treaty was expanded in 2016 through the Kigali Amendment to include hydrofluorocarbons or HFCs, a replacement for CFCs that do not harm the ozone but are a type of greenhouse gas that warms the planet more potently than carbon dioxide. The U.S. Senate ratified the amendment in September.

The report, which was presented Monday morning at the American Meteorological Society’s annual meeting in Denver, finds the world is also making progress at reining in these planet-warming emissions.

“We can already see HFCs are not increasing as fast as we thought they would because countries are starting to implement their own controls,” said Paul Newman, one of four co-chairs of the Scientific Assessment Panel of the Montreal Protocol.

Still, it is possible forthcoming data on ozone levels will prompt some concerns that the ozone layer is not recovering as quickly as the report concludes, he said. Newman said he expects that will be because the Hunga Tonga eruption blasted so much material into the atmosphere. Volcanic eruptions are known to accelerate ozone depletion.

Progress would likely also be slowed if humans pursue geoengineering to reverse global warming by injecting sunlight-reflecting particles into the upper atmosphere, Newman said. The panel, which considered the potential impact of that practice for the first time for Monday’s report, found that, depending on the timing, frequency and amount of such injections, the particles could alter aspects of atmospheric chemistry that are important in ozone development.

“The Antarctic ozone hole is the poster child of ozone depletion,” Newman said. “Stratospheric aerosol injections will probably make it a little bit worse.”

A previous version of this article incorrectly referred to hydrofluorocarbons as HCFCs. They are known as HFCs. The article has been corrected.