| The US power grid includes everything from 100-year-old hydro dams to brand-new batteries. It’s evolving as coal power diminishes, wind and solar rise and energy storage smooths out operations. But those changes are a shadow of what might come next.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory released a study on the project connection queue for the nation’s grids, showing just how much new power companies want to build, what type of power and where. In other words, it’s a glimpse at the future of US electricity.

Today, developers of more than 10,000 energy projects are asking grid operators for permission to connect to their networks. All told, the projects represent more than 2 terawatts of total power generation — about 50% more than current generation capacity. Almost all of this is wind, solar or battery energy storage.

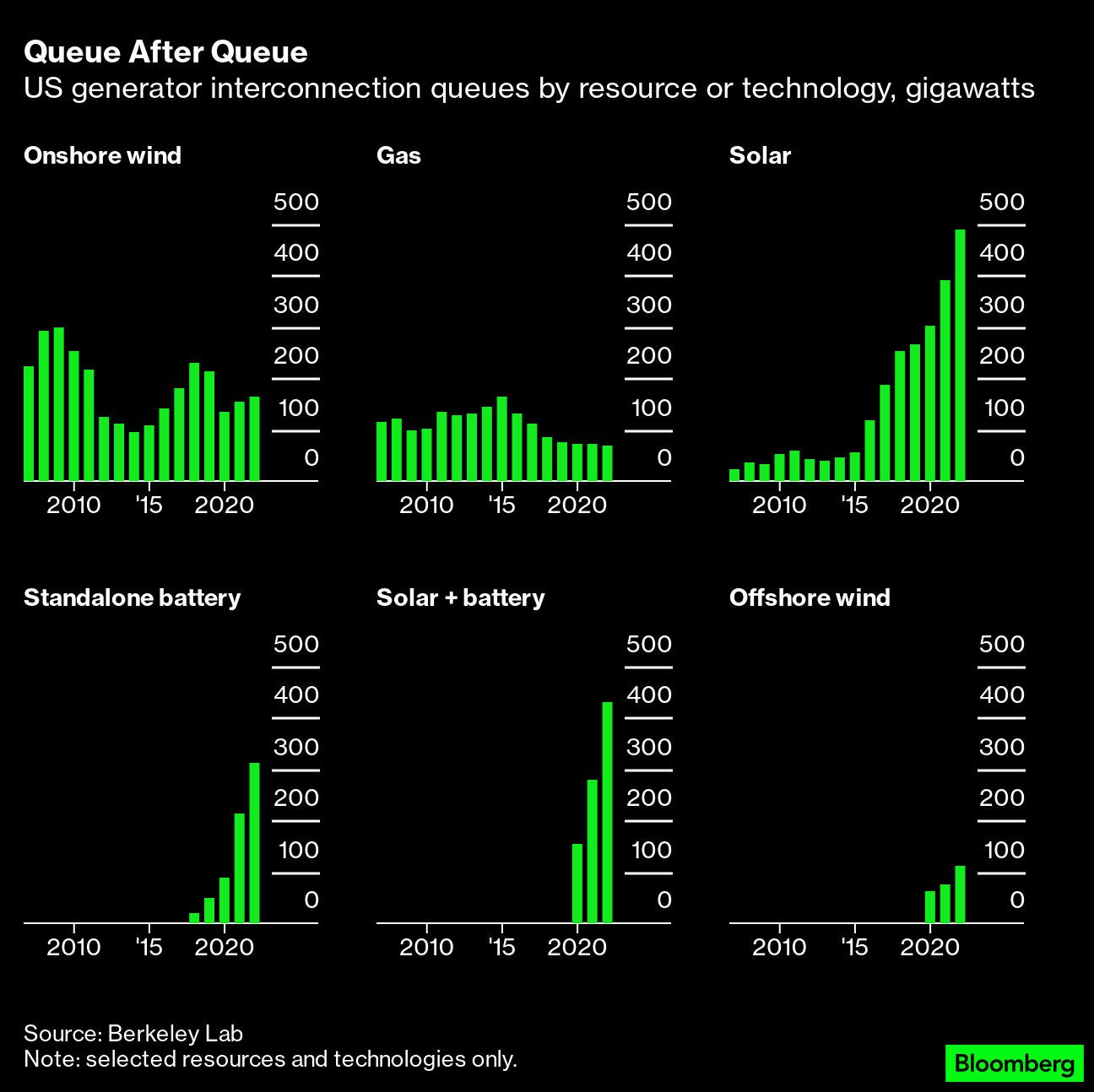

Fifteen years ago, wind dominated requests, followed by natural gas. Since then, both have declined in absolute terms as many projects succeeded in hooking up to the grid — a process known as interconnection — while other developers withdrew their requests because their projects were not viable. But solar requests have increased steadily for a decade.

In the late 2010s, two new resources entered: battery energy storage and offshore wind. Last year, there were more than 300 gigawatts of standalone storage projects in the queue, and more than 400 gigawatts of combined solar and storage. And in three years, offshore wind interconnection requests went from zero to more than 100 gigawatts.

There’s a good reason that neither coal nor nuclear is shown in the series above: They make up a vanishingly small share of the generation capacity that US operators are seeking to build. There are now about 6.5 gigawatts’ worth of nuclear plants requesting interconnection, the highest figure in the past seven years. There is less than 1.5 gigawatts’ worth of coal capacity — down from 42 gigawatts 15 years ago.

Gas and coal were more than 35% of the total interconnection queue in 2007. Today, they are less than 3.5%.

If developer interconnection requests are any indication, the US is planning a massive deployment of storage batteries. More than half of that planned capacity is “hybrid” — located alongside a power generator and sharing the same grid connection. Nearly all of that hybrid capacity is connected to wind or solar, but there are also a few gigawatts’ worth of storage planned alongside gas power plants.

Developers are also planning lots of standalone batteries, which will draw power from the grid rather than from a specific generator. The queue of these has expanded to more than 300 gigawatts and has spread beyond its initial markets on both coasts. The single biggest pool of planned battery assets is in the grid that includes Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, most of Nevada and New Mexico and parts of Montana and Wyoming. Close behind that is the electricity system of the Mid-Atlantic states, including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland and Virginia.

At this point it is worth repeating the caveat that Berkeley Lab attached to its 2021 edition of this study, exclamation point included: “Not all of these projects will ultimately be built!” Space, construction, and capital constraints would keep the US from building another 2 terawatts of power generation assets in the next 10 to 15 years. Ideally, hundreds of gigawatts of zero-carbon generation and storage will end up being built. But there will be a gap between what is planned today and what will be built tomorrow.

From 2000 to 2017, 21% of all projects that applied for interconnection reached commercial operation. There is variation by technology. Solar projects have a lower completion rate than wind or gas. In capacity terms — that is, in terms of the amount of energy that those assets can generate — 14% of the queue reached commercial operation from 2000 to 2017.

One concerning finding of the study is that it now takes much longer than it used to for a developer to receive an interconnection agreement. Since 2015, the time from request to agreement has roughly doubled to just under three years. Extra time means extra cost for developers, which results in lower returns on investment, higher power prices or both. Extra time also means that more developers are withdrawing from projects even after they have received approval to connect to the grid.

Fortunately, from the point when projects receive their agreement and start construction, building schedules have been generally stable. On average, it takes less than two years to build a project — but in California, projects now take four to six years to complete.

There is enough planned capacity for additional power generation in the US to transform the country’s electricity system. Achieving that depends less on new technology to generate and store power than it once did. Planning and transmission wires are now the biggest determinants of what gets built, where and when. The Inflation Reduction Act has unleashed billions of dollars for ramping up clean energy generation; the next, monumental challenge is building projects and power lines in time for the US to decarbonize the grid by 2035, the Biden administration’s target.

Nat Bullard is a senior contributor to BloombergNEF and writes the Sparklines column for Bloomberg Green. He advises early-stage climate technology companies and climate investors. |