from MIT: Do these heat waves mean climate change is happening faster than expected?

General warming predictions are still on track, but recent heat waves are a stress test for the modeling of extreme events.

Millions of people are now experiencing the effects of climate change firsthand. Blistering heat waves have smashed temperature records around the globe this summer, scorching crops, knocking out power, fueling wildfires, buckling roads and runways, and likely killing thousands across Europe alone.

The dizzyingly quick shift from an abstract threat to an era of tumbling temperature records, megadroughts, and pervasive fires has many people wondering: is climate change unfolding faster than scientists had expected? Are these extreme events more extreme than studies had predicted they would be, given the levels of greenhouse gases now in the atmosphere?

As it happens, those are two distinct questions, with different and nuanced answers.

For the most part, the computer models used to simulate how the planet responds to rising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere aren’t wildly off the mark, especially considering that they aren’t geared for predicting regional temperature extremes. But the recent pileup of very hot heat waves does have some scientists wondering whether models could be underestimating the frequency and intensity of such events, whether some factors are playing more significant roles than represented in certain models, and what it all may mean for our climate conditions in the coming decades.

Let’s address these issues point by point.

Is climate change largely to blame for these extreme heat waves?

Yes. Global warming has established a hotter baseline for summer temperatures, which dramatically increases the odds of more frequent, more extreme, and longer-lasting heat waves, as study after study after study has clearly shown.

“Climate change is driving this heat wave, just as it is driving every heat wave now,” said Friederike Otto, co-lead of World Weather Attribution, in a press statement about the unprecedented temperatures across Europe in recent days. “Heat waves that used to be rare are now common; heat waves that used to be impossible are now happening and killing people.”

Is climate change unfolding faster than scientists expected?

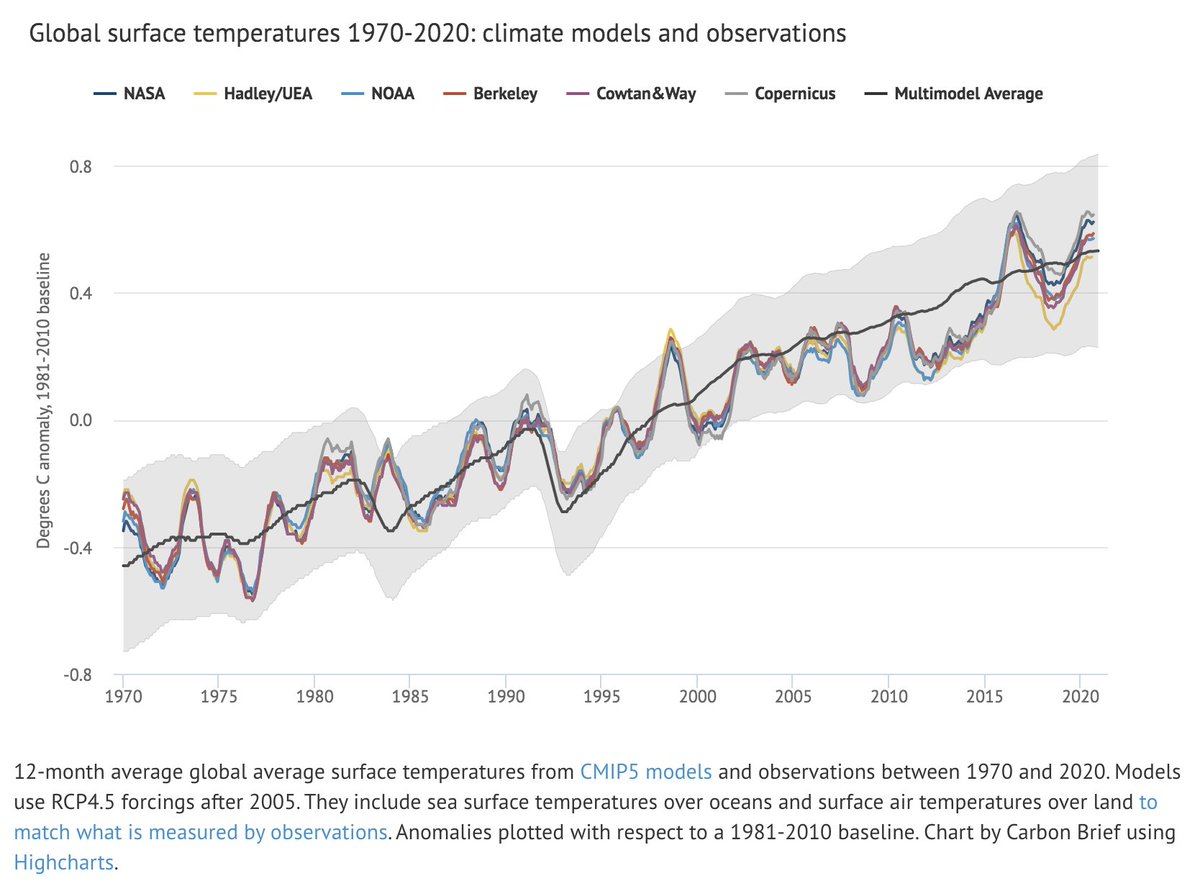

The answer, at least in the broad sense, is no. In fact, the linked rise in greenhouse gas levels and global average temperatures has tracked tightly within the spread of model predictions, even dating back to cruder climate simulations from the 1970s.

Several researchers and studies, including the latest UN climate report, have highlighted just how closely observed temperatures have followed predicted increases. The resemblance is uncanny (almost as if the world should have heeded the warnings of climate scientists decades ago).

Tweeted by Zeke Hausfather (@hausfath) on October 23, 2020.

In fact, the current concern among researchers is that the latest generation of models are collectively running too hot, potentially projecting excessive levels of warming from increased carbon dioxide concentrations, as Zeke Hausfather, Kate Marvel, Gavin Schmidt, and other scientists noted earlier this year in Nature.

Are climate models wrong about extreme events?

Sometimes, but it’s a complex question.

Certain real-world events have happened faster or to greater degrees than predicted by past or current models, including the loss of Arctic sea ice, the amount of land burned by wildfires, and the rapid increase in extreme temperature events in Europe in recent decades, scientists say.

“When it comes to certain types of extreme events, I think there is some evidence that things are changing faster than had been expected, or are explicitly represented in global climate models,” says Daniel Swain, climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“But,” he adds, “maybe that shouldn’t be too surprising.”

That’s because, for the most part, climate models were not designed to predict regional extreme events. Their main task is to simulate average temperature changes across long time periods and wide areas.

Researchers are well aware of, and have always been clear about, the shortcomings of climate models. While they’re continually improving, they remain rough computer simulations limited by human understanding of the climate system; the complex interactions among earth systems; computational power; and the cost of running the models numerous times to explore the spectrum of possibilities. And they still divide the planet into relatively large blocks to make the computation tractable—cells ranging in size from dozens to hundreds to thousands of square kilometers. This limits what can be predicted about local weather events with high accuracy.

It can also be difficult to tell whether some of the weather events we’re seeing are occurring outside the bounds of model findings. For instance, models do produce events like the one unfolding in Europe, but they’re supposed to be very rare there: occurring no more than once every 100 years under current climate conditions. The question is whether extreme extreme events, like Europe’s current heat wave or the one last year in the Pacific Northwest, are dramatic outliers or early warning signals that climate change can produce hotter events more frequently than initially expected.

Scientists simply have had too short of a time period with a climate system warmed by human actions to determine the answers to those sorts of questions.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty when it comes to these unprecedented and record-shattering events,” said Flavio Lehner, assistant professor of earth and atmospheric sciences at Cornell, in an email. “You can’t, with the highest confidence, say the models get this or don’t get this,” when it comes to certain extreme events.

What other forces could be contributing to very hot heat waves?

A variety of researchers are exploring the degree to which certain forces could be exacerbating heat waves, and whether they are accurately represented in the models today, Lehner says.

Those include potential feedback effects, such as the drying out of soil and plants in some regions. Beyond certain thresholds, this can accelerate warming during heat waves, because energy that would otherwise go into evaporating water goes to work warming the air.

Another open scientific question is whether climate change itself is increasing the persistence of certain atmospheric patterns that are clearly fueling heat waves. That includes the buildup of high-pressure ridges that push warm air downward, creating so-called heat domes that hover over and bake large regions.

Both forces may have played a major role in fueling the Pacific Northwest heat wave last year, according to one forthcoming paper. In Europe, researchers have noted that a split in the jet stream and warming ocean waters could be playing a role in the uptick in extreme heat events across the continent.

Why didn’t the scientists warn us properly?

Ugh. Some publications have actually printed words to this effect, in response to increasingly extreme weather events.

But, to be clear, scientists have been sounding the alarm for decades, in every way they could, that climate change will make the planet warmer, weirder, harder to predict, and in many ways more dangerous for humans, animals, and ecosystems. And they’ve been forthright about the limits of their understanding. The chief accusation they’ve faced until recently (and still do, in many quarters) is that they are doomsday fearmongers overstating the threat for research funding or political reasons.

Real-world events highlighting shortcomings in climate models, to the degree they have, don’t amount to some “aha, gotcha, scientists were wrong all along” kind of revelation. They offer a stress test of the tools, one researchers eagerly use to refine their understanding of these systems and the models they’ve created to represent them, Lehner says.

Chris Field, director of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, put it bluntly, in a letter responding to the New York Times’ assertion that “few thought [climate change] would arrive so quickly”: “The problem has not been that the scientists got it wrong. It has been that despite clear warnings consistent with the evidence available, scientists dedicated to informing the public have struggled to get their voices heard in an atmosphere filled with false charges of alarmism and political motivation.”