| By Tom Randall

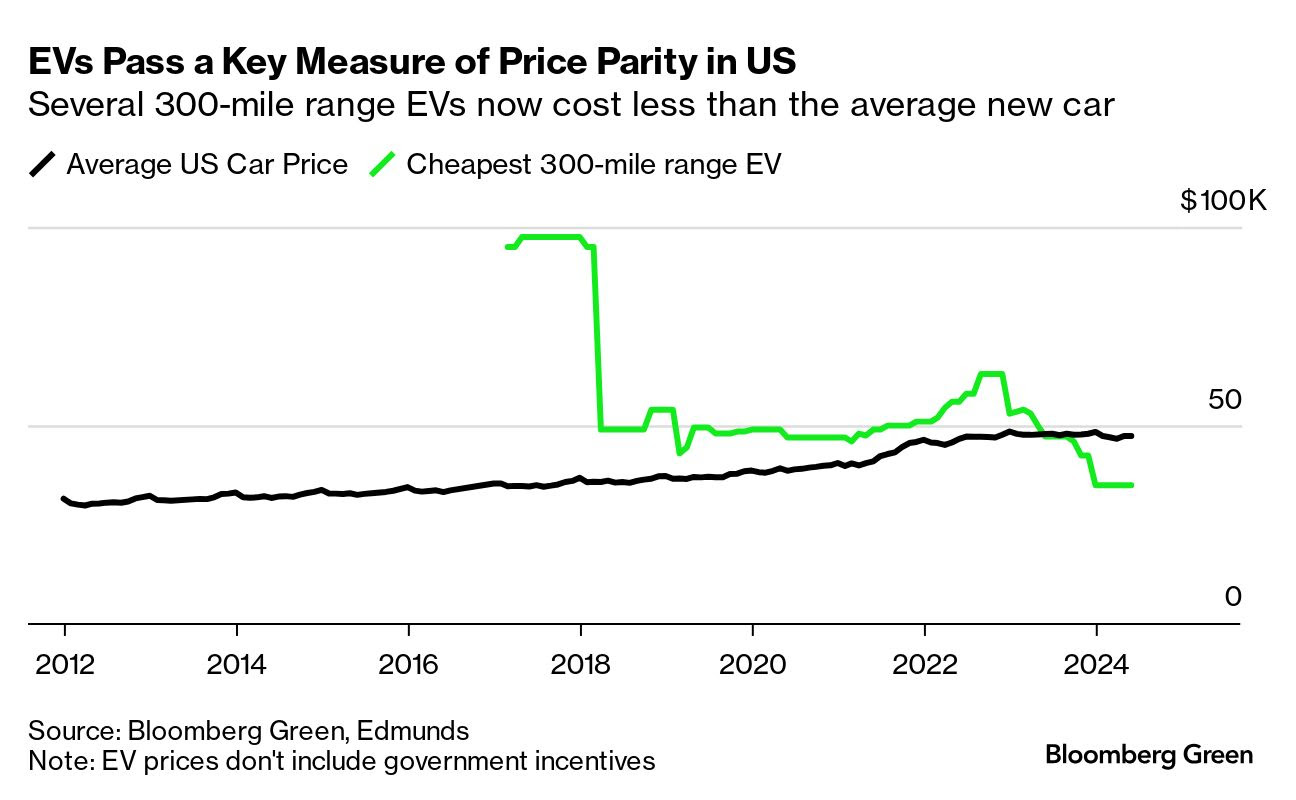

The electric vehicle transition has entered a fiercely competitive phase, one that’s producing an intriguing result for US car buyers: the first long-range EVs that are cheaper than the average gas-powered car.

At least three manufacturers — Tesla, Hyundai-Kia and General Motors — now offer EVs with more than 300 miles (480 kilometers) of range for less than the cost of the average new vehicle sold in the US, according to an analysis by Bloomberg Green. The most affordable is Hyundai’s 2024 Ioniq 6, which comes with 361 miles of range and a price tag that’s 25% below the national average of roughly $47,000.

Source: Bloomberg Green, Edmunds

Over the past six months, competition between US auto brands has taken on a Squid Game vibe, as pressure mounts to make EVs affordable and attract new buyers. Customers are increasingly savvy about battery range, charging speeds and charger accessibility, and are rejecting vehicles that don’t justify the sticker price. Automakers are taking note.

The industry has begun “a challenging period, very chaotic, very Darwinian,” Carlos Tavares, chief executive officer of Stellantis NV, told investors at a Bernstein conference last week.

Stellantis, which has been slow to offer electric models in the US, will soon launch a $25,000 electric Jeep as part of a large-scale EV offensive. “Affordability is the key success factor right now,” Tavares said. “If you want the scale to materialize, you need to be selling to the middle classes.”

Tavares said the only winning strategy is to offer EVs at comparable upfront prices from the start, even if it requires sacrificing profit margins during the transition phase. He warned that car manufacturers and suppliers will have to reduce costs drastically.

A Jeep Wrangler at the Montreal Electric Vehicle Show in April. Photographer: Graham Hughes/Bloomberg

EVs as a whole are still expensive to buy, with prices averaging about 15% more than a typical US car, according to Cox Automotive. That’s partly because early EVs were disproportionately aimed at the luxury end of the US market. Until recently, the few affordable models on offer were hobbled by insufficient battery range and slow charging speeds.

But some new models are beginning to break through the affordability barrier, said Stephanie Valdez-Streaty, director of industry insights at Cox. “Price is going to continue to be one of the top barriers for adoption, but the EV premium is shrinking and that’s a good thing,” she said.

The standard bearer for affordable long-range EVs may be the new electric Chevy Equinox. The SUV comes with 319 miles of range for around $42,000, before federal tax credits that can knock $7,500 off the price. Those incentives will drop the cost of a base model, available later this year, below $28,000. Chevy will follow the Equinox with a new Bolt that GM says will be “the most affordable vehicle on the market by 2025.”

Prices for new EVs and ICE cars are similar enough that federal incentives can make up the difference, though complex rules for which cars and customers qualify make it difficult for shoppers to evaluate their options.

That isn’t the case for car leases, though, with dealers receiving the EV tax credit. Some are passing it along by wrapping the savings into the monthly lease payment. As a result, the cost of leasing long-range Hyundai and Tesla EVs is as much as 37% lower than leasing similar gas-powered models made by Toyota and BMW.

Source: Bloomberg Green, company websites

Overall, EV price parity is difficult to measure. Determining what constitutes gas-car equivalence varies from driver to driver. The switch to a slow-charging EV with 200 miles of range would be a significant burden for someone who travels long distances, but it could be an upgrade for a shorter-distance commuter who charges at home while they sleep. In the US, 300 miles of range has emerged as a benchmark for where the advantages outweigh the disadvantages for most drivers.

Data: US EPA, Marklines, company websites, BloombergNEF, IEA

A stricter definition of price parity is the point at which the average EV costs the same as the average internal combustion engine, excluding gas savings and government subsidies. That upfront affordability is key for the later stages of widespread adoption, especially in lower-income countries.

American car buyers demand more range from electric cars than drivers in any other country. The average EV now comes with about 300 miles; with a few of those models selling for less than the average car, others will surely follow. The IEA says price parity will be the norm by 2030.

Read and share a full version of this story on Bloomberg.com.

For unlimited access to climate and energy news and original data and graphics reporting, please subscribe.

- Chinese EVs are pouring into Brazil. Shut out of US markets and under fire in Europe, China’s electric car makers are zeroing in on countries where they’re welcome. Brazil is a big one.

- Free power is raising red flags in Europe. Electricity prices are going negative so often that it’s sparking concerns among investors about how much more renewable power they can build without hurting returns.

- Retrofits are dominating the US nuclear industry. Georgia’s Alvin W. Vogtle power plant boasts the first new reactors in the US in over 30 years. They’ll also be the last reactors built in the country for a long time.

- Banks are targeting a new kind of real estate risk. At major financial institutions, loans to commercial real estate face a new litmus test: the carbon emissions of buildings and the expected cost of upgrades.

- $100-per-ton carbon capture is still a ways off. Costs remain stubbornly high, so companies are starting to move the goalposts, which risks undercutting trust across the nascent industry.

- Superyachts have a supersized climate impact. There are now almost 6,000 superyachts, whose planet-warming pollution led lifestyle social scientist Gregory Salle to dub them a form of “ecocide.”

The Lurssen Ahpo megayacht in Miami. Photographer: Eva Marie Uzcategui/Bloomberg

|