Budget v. Actual: GHG Emissions2021 & Remaining Headroom for 1.5º C

Greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere correlate to average global temperatures. Pre-industrial levels of 280 ppm of CO2 meant temperatures about 1º C less than today. The IPCC says that, if we

The Global Carbon Project scientists revised their carbon budget, which is a kind of scientific ledger for estimating how much CO₂ the atmosphere can hold before locking in a temperature threshold. To have a 50% shot at keeping global heating below 1.5°C, beginning in 2022, the world can emit no more than 11 years worth of CO₂ at the current rate. To keep the temperature rise below 1.7°C or 2°C, there are 20 or 32 years worth of emissions left.

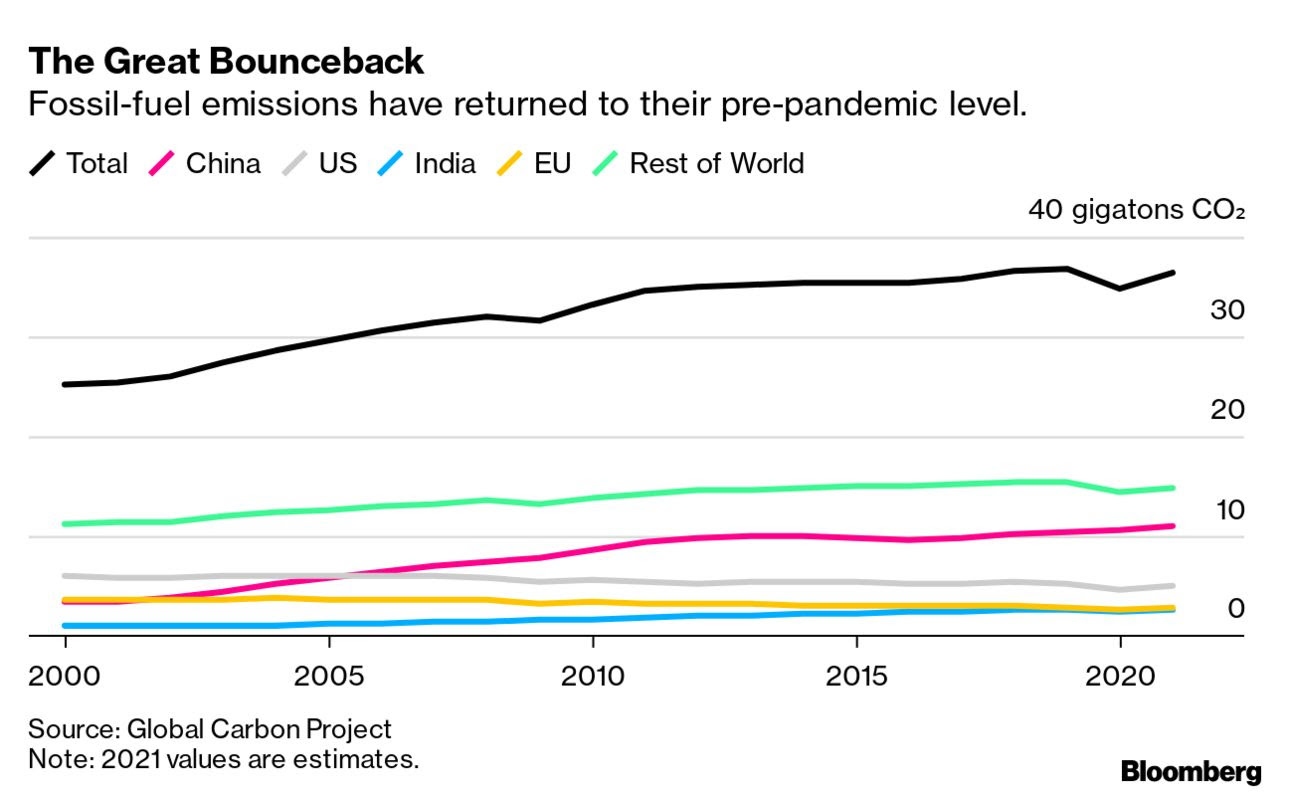

Global carbon dioxide pollution returned to a pre-pandemic level this year, according to an early estimate by the research group Global Carbon Project prepared for the COP26 talks occurring in Glasgow.

The new numbers vividly illustrate the global challenge posed by decades of delayed climate policy and investment. To meet the 2050 goal of the Paris Agreement, which calls for limits to warming temperatures, nations would now have to cut emissions every year by an amount greater than the combined carbon output of Germany and Saudi Arabia.

Emissions from fossil-fuel burning are expected to rise this year by 4.9% above the 2020 level, to 36.4 gigatons of CO₂, or nearly the 2019 level. Last year, emissions fell 5.4% after Covid-19-related quarantines and policies limited economic activity in much of the world.

“Emissions snapped back like a rubber band,” said Robert Jackson, an Earth system science professor at Stanford University and chair of the Global Carbon Project. “That’s the same thing we saw after 2008, where emissions dropped 1.5% in 2009 and then jumped 5% in 2010 as if nothing had changed.”

China is by far the world’s biggest polluter, responsible for almost a third of fossil-fuel CO₂ emissions. The country’s post-pandemic economic recovery efforts put its coal plants into overdrive, and its national emissions are expected to finish the year 5.5% higher than 2019, at 11 gigatons. India’s emissions, the third largest, were found to rise 4.4% over 2019.

Coal use worldwide peaked in 2014, and researchers had noted with some relief that coal was in decline. This year has challenged that assumption, with coal-burning rising above its 2019 level, although still below the record year.

“The bounce in coal is quite surprising,” said Glen Peters, research director for the Center for International Climate Research in Oslo, and a Global Carbon Project member. “We thought China had peaked coal, but it’s now clawed back over the peak.”

During the previous decade, CO₂ emissions fell in 23 countries that make up about a quarter of the world’s total. This group includes the U.S., which is the second biggest annual polluter and the biggest historically, Japan, Mexico, and 14 European countries.

Energy use from renewable sources grew more than 10% this year, on par with the recent average—despite an unprecedented temporary decline in energy use.

The data add even greater urgency to the already breathless work this week and next in Glasgow, where nations are struggling to execute promises made in the 2015 Paris Agreement. The Global Carbon Project scientists revised their carbon budget, which is a kind of scientific ledger for estimating how much CO₂ the atmosphere can hold before locking in a temperature threshold. To have a 50% shot at keeping global heating below 1.5°C, beginning in 2022, the world can emit no more than 11 years worth of CO₂ at the current rate. To keep the temperature rise below 1.7°C or 2°C, there are 20 or 32 years worth of emissions left.

“It’s not a threshold that once you reach a specific temperature that everything goes berserk,” said Corinne Le Quéré, a climate scientist at the University of East Anglia and a Global Carbon Project member. “But the more warming, the more risks we take of destabilizing all kinds of aspects of the climate system.”

A revision to UN deforestation figures led the Global Carbon Project to a surprising new conclusion about CO₂ emissions from land. Forest regrowth is larger than previously thought, which means trees and soil have soaked up more CO₂ than expected over the last 2 decades. The deforestation rate, less the absorption rate, leaves a net decline in emissions that makes the 2021 estimate of 2.9 gigatons just 64% of the early 2000s rate. These numbers, however, are much less certain than the the fossil-fuel consumption data, given the complexity of estimating deforestation and regrowth.

The revised but tentative deforestation numbers—combined with the historically small increases in the CO₂ pollution rate the last decade—is a nice surprise in a world in need of one.

“That land use change emissions are likely considerably lower than previously expected means that it’s a lot easier for us to turn global forests into a net sink rather than a source of CO₂,” said Zeke Hausfather, director of climate and energy a the Breakthrough Institute, who is not affiliated with the Global Carbon Project.

As a service to readers, Bloomberg.com will lift its paywall for climate stories from November 1 through November 12. Follow our special COP26 coverage here.

Bloomberg Green at COP26: Bloomberg will convene executives and thought leaders for events focused on local and tactical solutions. To learn more about the week of events an

Seen and heard: Getting warmer |

| To avoid catastrophic climate change, scientists say that global warming should be limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. This underlies many of the “net zero” pledges that countries and companies have made, and is the talk of the town in Glasgow, where the COP26 climate summit is underway. |

| Humans have warmed the planet 1.1 degrees thus far, so there is little room for maneuver. What are the chances that the rise in temperature can be limited to 1.5 degrees? |

|