Antarctic ice melt could disrupt the world’s oceans: Study

SINGAPORE – A major ocean circulation that forms around Antarctica could be headed for collapse, risking significant changes to the world’s weather, sea levels and the health of marine ecosystems, scientists say, offering a stark warning about the growing impacts of climate change.

Global warming is accelerating the melting of ice in Antarctica, and the increased amount of fresh water flooding into the ocean is disrupting the flow of the Antarctic overturning circulation, according to a study published on Wednesday in the journal Nature.

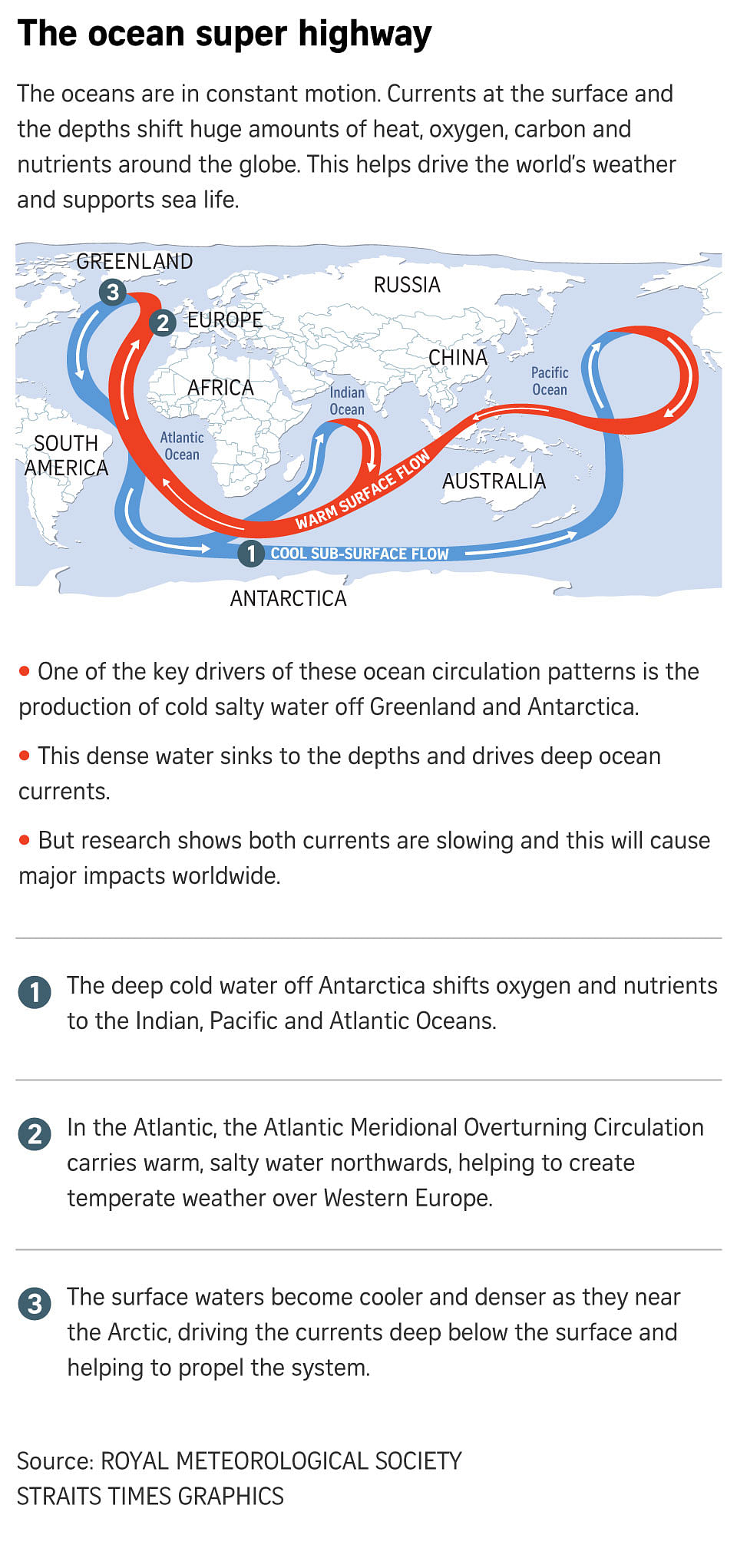

The Antarctic overturning circulation is part of a global network of currents that shift heat, oxygen and nutrients around the globe.

Near Antarctica, cold salty water sinks to depths of more than 4,000m. The sinking of dense, oxygenated water helps drive the deepest flow of the overturning circulation. The water flows north, carrying oxygen and nutrients to the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic oceans. A similar process also occurs off Greenland.

“Changes that happen in one location, such as Antarctica, can then have a global influence because those waters move all throughout the planet,” said study co-author Adele Morrison, a research fellow from the Research School of Earth Sciences at the Australian National University in Canberra.

But there are signs the overturning circulation is slowing, disrupted by the increasing amount of meltwater from Antarctica that is making the waters less salty, and therefore less dense and not sinking with the same force.

And the melting is increasing as growing amounts of greenhouse gas emissions, mainly from burning fossil fuels, are heating up the atmosphere and oceans.

“Our modelling shows that if global carbon emissions continue at the current rate, then the Antarctic overturning will slow by more than 40 per cent in the next 30 years – and on a trajectory that looks headed towards collapse,” said co-author Matthew England, deputy director of the ARC Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

The international team of scientists modelled the amount of Antarctic deep water produced under a high-emissions greenhouse scenario until 2050.

A collapse of the deep ocean current would cause the oceans below 4,000m to stagnate.

“This would trap nutrients in the deep ocean, reducing the nutrients available to support marine life near the ocean surface,” Professor England said in a statement.

Meaning, marine ecosystems at the surface would slowly starve.

Melting of polar ice in Antarctica and Greenland will also accelerate sea-level rise.

“Our study shows that melting of the ice affects the ocean in a way that can accelerate the pace of sea-level rise, that is, a positive feedback,” co-author Steve Rintoul told The Straits Times.

“As the fresh water added by melting ice slows the formation of cold, dense bottom water, warmer water at shallower depths shifts south to replace it. The shift of warm waters closer to Antarctica means more heat is available to drive even more melting,” said Dr Rintoul, an oceanographer and climate scientist at Australia’s national science agency CSIRO in Hobart.

Other impacts from a slowdown mean less heat and carbon could be stored in the ocean, driving more rapid climate change.

“The effects can extend far from Antarctica; other studies have shown that a slowdown of the Antarctic overturning shifts tropical rain bands away from their usual position,” he said.

The world’s oceans store vast amounts of heat, absorbing more than 90 per cent of the warming that has occurred in recent decades due to increasing greenhouse gases. Much of the heat is in the top surface layers, but the deep ocean is slowly warming up as well. The oceans also absorb about a quarter of all carbon dioxide emissions from human activity.

“The study shows that climate change is already affecting all of the globe, even Antarctica and the deepest parts of the ocean,” said Dr Rintoul, adding that the changes to the deep ocean were surprisingly large and rapid.

Decisions to make deep and rapid cuts in greenhouse gas emissions can limit the damage.

“If emissions are lower, the impacts will be lower, and this is an important point,” Dr Rintoul said.

“Every 0.1 deg C of warming we can avoid lowers the risk of damaging changes to climate. The sooner and stronger we act, the lower the risk,” he said.