Primer: Lithium Mining in Nevada

Primer Note: I’m introducing a concept called “Primer” here. A primer is an overview or summary of the current state of affairs regarding a single topic — in this case lithium mining in Nevada.

Unlike other posts appearing here, which are time-based and somewhat temporary, Primers are meant to be “evergreen” content. They will be preserved in a “Primer Library” accessed from the menu bar (at top of page).

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

Nevada has significant amounts of lithium ore, mostly in the northwestern part of the state. The US needs a LOT of lithium to make the batteries that store electricity for EVs and as backup power for the grid.

Investors are backing new mining projects, including in Nevada, incentivized with federal loan guarantees (which help reduce the interest rates on loans to these commercial projects). See “Billions in US funding boosts lithium mining, stressing water supplies.”

There are two main ways that lithium is produced today:

- “Brine evaporation” (usually by pumping lithium-rich water from underground brine aquifers and evaporating the water) and

- Lithium-bearing ores, such as spodumene (through a process that involves crushing, roasting and acid leaching).

Both processes impact the environment by using copious amounts of water and energy. A 2021 study found that lithium concentration and production from brine can create about 11 tons of carbon dioxide per ton of lithium, while mining lithium from spodumene ore releases about 37 tons of CO2 per ton of lithium produced.Note 1

Nevada has one operating mine – Silver Peak, which is about halfway between Reno and Las Vegas. It uses the brine evaporation method. A second mine, Thacker Pass, in the north-central part of the state, is an open-pit mine that will crush the ore and use sulfuric acid processing. It is at the beginning of the construction phase, although one investor is balking owing to a fear that Donald Trump may win and kill further federal support. [This is why bi-partisan support is so important!]

There are a number of other lithium projects in various stages of planning and permitting. The Center for Biological Diversity lists 125 projects they are monitoring in Nevada alone. See this map. See also the more active projects that are shown here, as they are actively raising money now.

Direct Lithium Extraction

There is another lithium extraction method that now appears economically promising, both because the environmental impact is smaller and because the proven reserves in the US are larger: Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE).

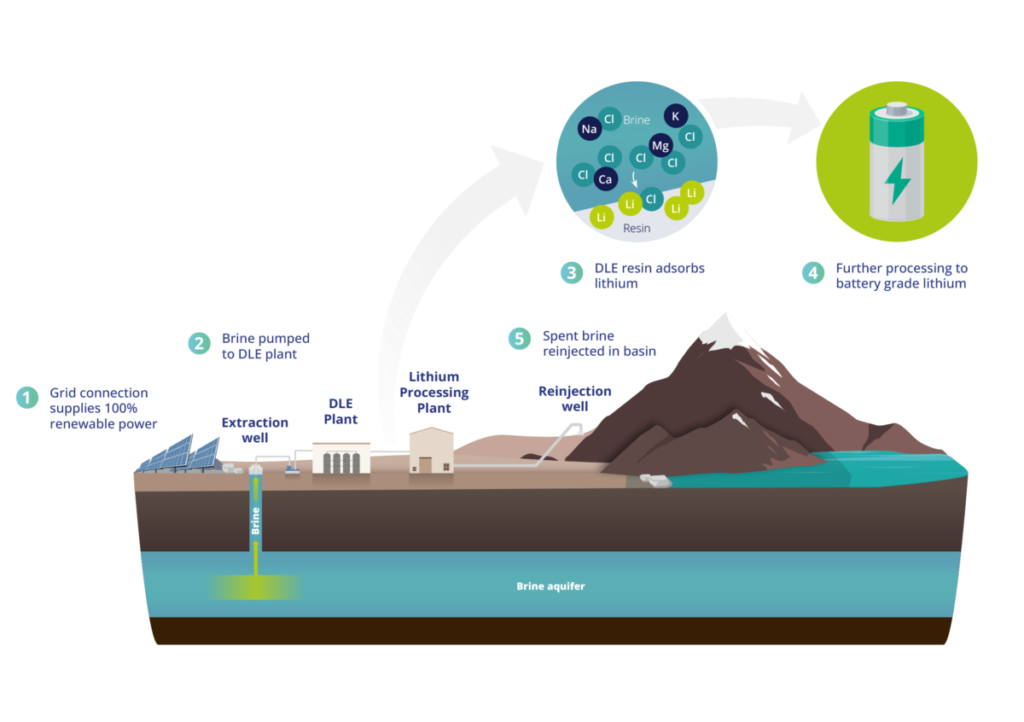

DLE is a proven technology, with established producing projects based on DLE in China and South America. Brine is extracted from the basin aquifer and pumped to a processing unit where a resin or adsorption material is used to extract only lithium, while spent brine is reinjected into the basin aquifers with no aquifer depletion or harm to the environment. The resin adsorbs lithium chloride (LiCl) molecules onto the surface of the material, which is then stripped using water creating a lithium eluate. This eluate is then further concentrated via reverse osmosis and mechanical evaporation stages before standard industry processes are used to produce battery-grade lithium.

Source: Cameron Manche (Texas A&M University) and lithium companies

There is an area in northeast Texas that has a limestone formation under it called “The Smackover.” It has lithium-rich brine aquifers. A local entrepreneur has perfected a modular DLE processing unit that can extract 97% of the lithium and return most of the rejected brine back underground. You can read the whole story here — but bottom line: DLE might make Nevada lithium-brine operations more ecologically benign. And it might post significant competitive pressure on lithium prices.

60 Minutes did a piece last year on lithium deposits under California’s Salton Sea. That source also looks extremely large and promising.

1 Kelly, Jarod C., et al., “Energy, greenhouse gas, and water life cycle analysis of lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide monohydrate from brine and ore resources and their use in lithium ion battery cathodes and lithium ion batteries.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Volume 174, 2021, doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105762.