Western Drought is Worst in 12 Centuries, Study Finds

from NYTimes

Fueled by climate change, the drought that started in 2000 is now the driest two decades since 800 A.D.

Feb. 14, 2022

ALBUQUERQUE — The megadrought in the American Southwest has become so severe that it’s now the driest two decades in the region in at least 1,200 years, scientists said Monday, and climate change is largely responsible.

The drought, which began in 2000 and has reduced water supplies, devastated farmers and ranchers and helped fuel wildfires across the region, had previously been considered the worst in 500 years, according to the researchers.

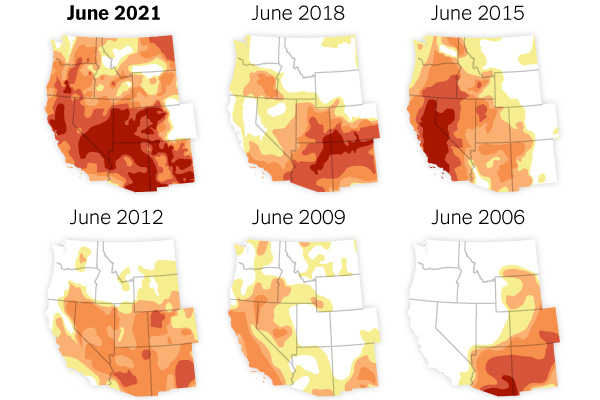

But exceptional conditions in the summer of 2021, when about two-thirds of the West was in extreme drought, “really pushed it over the top,” said A. Park Williams, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who led an analysis using tree ring data to gauge drought. As a result, 2000-2021 is the driest 22-year period since 800 A.D., which is as far back as the data goes.

The analysis also showed that human-caused warming played a major role in making the current drought so extreme.

There would have been a drought regardless of climate change, Dr. Williams said. “But its severity would have been only about 60 percent of what it was.”

Julie Cole, a climate scientist at the University of Michigan who was not involved in the research, said that while the findings were not surprising, “the study just makes clear how unusual the current conditions are.”

Dr. Cole said the study also confirms the role of temperature, more than precipitation, in driving exceptional droughts. Precipitation amounts can go up and down over time and can vary regionally, she said. But as human activities continue to pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, temperatures are more generally rising.

Although there is no uniform definition, a megadrought is generally considered to be one that is both severe and long, on the order of several decades. But even in a megadrought there can be periods when wet conditions prevail. It’s just that there are not enough consecutive wet years to end the drought.

That has been the case in the current Western drought, during which there have been several wet years, most notably 2005. The study, which was published in the journal Nature Climate Change, determined that climate change was responsible for the continuation of the current drought after that year.

“By our calculations, it’s a little bit of extra dryness in the background average conditions due to human-caused climate change that basically kept 2005 from ending the drought event,” Dr. Williams said.

Climate change also makes it more likely that the drought will continue, the study found. “This drought at 22 years is still in full swing,” Dr. Williams said, “and it is very, very likely that this drought will survive to last 23 years.”

Several previous megadroughts in the 1,200 year record lasted as long as 30 years, according to the researchers. Their analysis concluded that it is likely that the current drought will last that long. If it does, Dr. Williams said, it is almost certain that it will be drier than any previous 30-year period.

Tree rings are a year-by-year measure of growth — wider in wet years, thinner in dry ones. Using observational climate data over the last century, researchers have been able to closely link tree ring width to moisture content in the soil, which is a common measure of drought. Then they have applied that width-moisture relationship to data from much older trees. The result “is an almost perfect record of soil moisture” over 12 centuries in the Southwest,” Dr. Williams said.

Using that record, the researchers determined that last summer was the second driest in the last 300 years, with only 2002, in the early years of the current drought, being drier.

Monsoon rains in the desert Southwest last summer had offered hope that the drought might come to an end, as did heavy rain and snow in California from the fall into December.

But January produced record-dry conditions across much of the West, Dr. Williams said, and so far February has been dry as well. Reservoirs that a few months ago were at above-normal levels for the time of year are now below normal again, and mountain snowpack is also suffering. Seasonal forecasts also suggest the dryness will continue.

“This year could end up being wet,” Dr. Williams said, “but the dice are increasingly loaded toward this year playing out to be an abnormally dry year.”

Samantha Stevenson, a climate modeler at the University of California, Santa Barbara who was not involved in the study, said the research shows the same thing that projections show — that the Southwest, like some other parts of the world, is becoming even more parched.

Not everywhere is becoming increasingly arid, she said. “But in the Western U.S. it is for sure. And that’s primarily because of the warming of the land surface, with some contribution from precipitation changes as well.”

“We’re sort of shifting into basically unprecedented times relative to anything we’ve seen in the last several hundred years,” she added.

Henry Fountain specializes in the science of climate change and its impacts. He has been writing about science for The Times for more than 20 years and has traveled to the Arctic and Antarctica. @henryfountain • Facebook